During the spring of 2013, Elon University became one of the few institutions of higher learning nationally to allow students to use a preferred name on campus records including email address and diplomas. Additionally, the office of the Registrar has worked to clarify the documentation for students to change their gender marker in the Elon student system.

It’s a move that recognizes the millions living around the world who don’t identify with traditional notions of being male or female or those somewhere in the transition process.

The human brain takes two seconds to identify a person as either male or female, according to senior Jaden Wilkes, and he listens to people fumble with his identity every day. Wilkes identifies as a trans man — his biological sex is female but his gender ex-pression is male.

“I don’t pass completely as male,” Wilkes said. “It takes you a little longer to think about who exactly I am, and that used to piss me off. But I’ve come to grips with why people stare.It’s not always like, ‘Oh,there’s a freak.’ It’s just that the brain connection isn’t always there.”

Wilkes’ appearance deceives some, with closely cropped dark hair and clothing that’s a little on the baggy side.

To help students and teachers make that connection sooner, Registrar Rodney Parks, who has published LGBTQ research in national journals, oversaw the implementation of the preferred name process throughout the Elon system. The goal, he said, is to minimize the painfully awkward interactions that stem from mistaking sexual identity.

“This is something that students have expressed interest in for a while now,” Parks said. “Imagine being stuck in a name you don’t identify with and hearing it all day long. We wanted to let the student choose, let them make the decision, and we decided this was the best way to put that in their hands.”

Wilkes has been out for more than a year now and has accepted that teachers will use the wrong pronouns — Wilkes prefers he, his, him — and that students will stare a little too long and ask questions that are a little too pointed.

“It’s not something that I’ve explained to anyone, really,” he said. “They use the wrong pronouns all the time, and I don’t really correct them because I don’t want to be called out almost, and it’s not any of their business, and I don’t feel like I have a need to.”

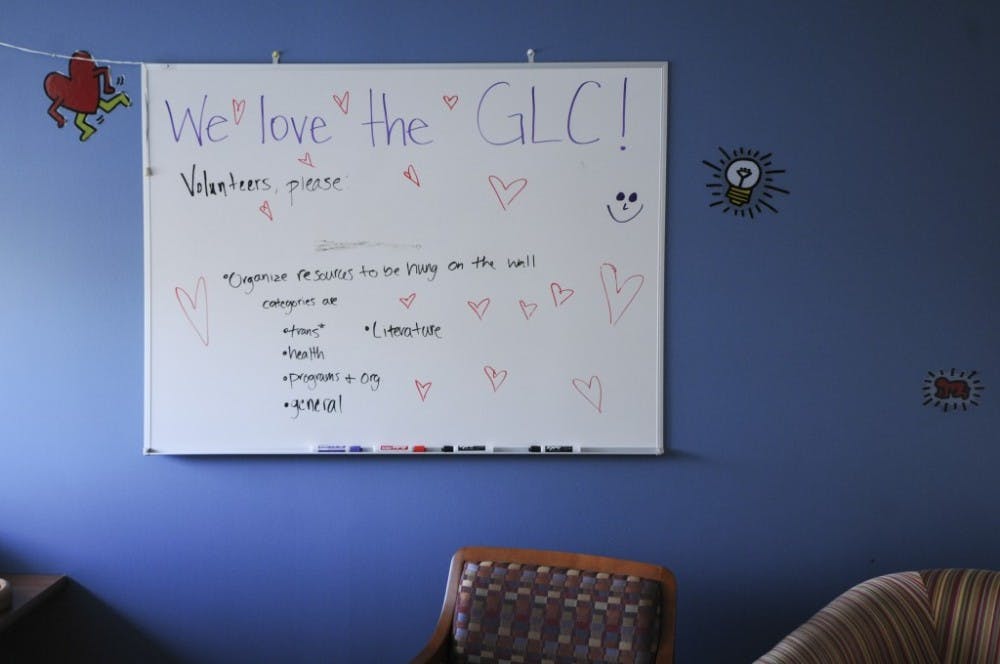

It’s a pressure that has plagued college students across the LGBTQ spectrum for years, according to Matthew Antonio Bosch, director of the Gender and LGBTQIA Center.

“It can be so stressful, so much pressure, for students to face every single moment of the day,” Bosch said. “Elon students in particular are often overcommitted, super busy, and coming out or thinking about coming out adds a burden that can be sometimes crushing.”

And, if left unchecked, it can lead to depression and a host of mental health issues as students struggle to internalize their gender identity, let alone having to explain it to others. The mounting stress levels can cause dips in GPAs and classroom performance for students coming out or considering.

When Wilkes began the coming out process, his grades dropped amidst the stress, though he has since brought them up to levels he’s “happy with.”

“I was super stressed and freaked out and dealing with everything at once,” he said. “School was often the furthest thing from my mind at the time.”

Parks acknowledged the difficulty of keeping up with the seemingly endless stream of class assignments, group projects, tests and quizzes Elon throws at students every day, especially when a student is coming to terms with their gender identity.

“Elon is an academically rigorous institution,” he said. “We set high standards here, standards students are challenged to meet. When you throw in issues of identity, of a student asking, ‘Where am I right now?’ that does make it even harder. It’s why we strive to make every accommodation for recognizing that, no, not everyone identifies with being a traditional male or female anymore. Elon has grown and is continuing to grow to reflect that.”

For his part, Bosch holds confidential meetings with students struggling with gender identity, visits classrooms when invited to speak on LGBTQ issues by professors and helps focus the attention of the Presidential LGBTQIA Task Force, a 14-person collaboration of students, faculty, staff, senior administrators and alumni, co-chaired by Bosch and Mary Jo Festle,professor of history and associate director of the center for the advancement of teaching and learning.

Already, Elon University has established a three-pronged alert system for students to report incidents on campus — anonymously, online, in-person or over the phone. All reports of bias are filtered through Royster’s office.

But not all of the problems facing LBTQ students on campus are tied to homophobic slurs and other issues of bias, though they have occurred in the past. In September 2013, a depiction of male genitalia was found scrawled on a whiteboard in Colonnades D, along with a swastika and the letters “KKK.”

Though the September incident wasn’t thought, at the time, to be promoting homophobia, Bosch said it’s important to remember that all discrimination is tied to each other — that acts of hatred against re ligion or race are every bit as demeaning as LGBTQ epithets.

In the wake of that incident and others, including one April 2013 where students living in an off-campus apartment found a handwritten note that included a racial slur referencing hip-hop and rap music, then- SGA President Welsford Bishopric and President Leo Lambert announced the formation of a committee designed to further Elon’s intellectual climate.

Bosch said the progress made in the time since has been remarkable, and Wilkes agreed.

“Since [Bosch] came, there have been such strides made between us and the administration,” he said. “It’s crucial for someone who can devote all of their time to helping people like me be given the position he has. There have already been noticeable changes in Elon policies, like the name change option, that has made me feel more comfortable here.”

Elon’s 5,599 undergraduate enrollment is on the smaller size nationally, but it’s still surprising how few incidents of bias have occurred in the nine months Bosch has been at the university, he said.

“It’s surprising to me how few bias incidents there are in the grand scheme of things,” he said. “When people hear about an incident of bias happening, there’s this immediate response, and that can highlight when things go wrong, but it’s good in the sense that people aren’t afraid to report and shows the amount of allies we have on campus, the number of people who really care.”

People who identify on the LGBTQ spectrum can be their greatest advocates, according to Bosch, but that doesn’t mean the responsibility of educating others should or does fall on their shoulders.

“People who have the experience of it are always going to be the greatest educators,” he said.

Wilkes said he’s used to fielding the kind of innocent questions children ask — about whether he’s a boy or a girl, the kind of question not intended to be offensive, only curious.

“It happens with kids all of the time,” he said. “Yeah, it’s kind of uncomfortable being asked who I am or what’s wrong with me, but it’s a whole lot different being asked by a child why my hair is so short if I’m a girl, than being asked what gender pronoun I prefer in front of the whole entire class.”