Nearly every day for the past several decades, Clay Smith of Redbud Farm has awakened at sunrise eager to plant, tend and market his crops. He’s 70 now and has witnessed massive changes in farming methods and economics. He’s typical in many ways of the farmers who are the foundation of a strong country.

He and others like him are the exception to the rule today — small farmers who believe it is worth the struggle to continue in an agriculture industry in which government, corporations and societal demands are constantly creating new hurdles to overcome.

It is becoming more difficult to recruit young people to meet these challenges. The lack of profits and high start-up costs associated with modern-day farming have contributed to a declining interest in farming for younger generations, according to Smith.

“The average age of a farmer in North Carolina is up in the high 50s,” the longtime organic farmer said. “How much longer do I have? Maybe another 10 years. We’ll see. Nobody could do it forever. We need to have more young people coming into farming.”

Dwindling interest in small-scale farming

North Carolina agriculture is a $78 billion industry that employs 16 percent of the state’s work force. However, much of the profits are generated by large-scale farmers. Most individual and family farmers are not reaping the benefits.

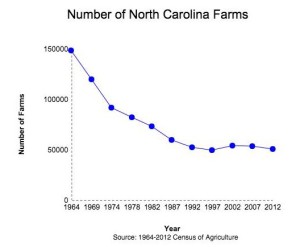

The most recent U.S. Department of Agriculture census, reported in 2012, showed a 5 percent decrease in the number of North Carolina farms between 2007 and 2012. Only 43 percent of those farms recorded net economic gains in 2007 and 2012.

The most recent U.S. Department of Agriculture census, reported in 2012, showed a 5 percent decrease in the number of North Carolina farms between 2007 and 2012. Only 43 percent of those farms recorded net economic gains in 2007 and 2012.

Within the last couple decades, the number of North Carolina farms has stabilized around 60,000 after a dramatic decline between the 1960s and 1980s.

Smith’s Redbud Farm has been one of the few farms to consistently record net gains. But he said his real success is limited by a number of factors.

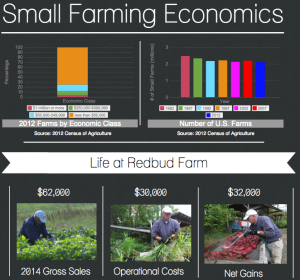

"Last year, on about three acres of land, we had gross sales of $62,000," Smith explained. "The operational expenses in terms of seed, fertilizer, pesticide, fuel for the tractor, the irrigation line and infrastructure and the electricity to run the cooler is about $30,000. So we made about $30,000. That’s not a lot of money.”

If you take into account the fact that two full-time workers – Smith and his wife Nancy Joyner – were the "paid labor," their annual salaries add up to just $16,000 each. That places them firmly below the poverty line.

Yet in terms of total farm revenue they are considered one of the wealthier North Carolina farms by comparison.

The 2012 Census of Agriculture noted 79 percent of farms recorded less than $50,000 in revenue.

The 2012 Census of Agriculture noted 79 percent of farms recorded less than $50,000 in revenue.

Ralph Noble, chair of the department of animal science at North Carolina A&T State University, works at the university’s farm and offers assistance to small and aspiring farmers. Like Smith, he has witnessed a steady decline in emerging farmers.

"When I started school back in the 1960s, 90 percent of my friends had parents or grandparents who came from farms," Noble said. "Now you can probably go back generations and you won’t find them there."

A lack of government programs encouraging young people to get into agriculture is partly to blame, according to Smith.

"There should be more grants and low-interest loans for young people who want to go into farming," he said. "A person coming out of college, tech school or high school is just beginning and doesn’t really have a financial nest egg or anything to go out and buy land or buy the minimal amount of equipment that they need."

Video Clip: Smith and Joyner discuss struggles facing Redbud Farm and the small farming industry.

Cost-share and rebate programs aim to assist

- Joyner packages tomatoes for Elon's farmers' market. Government assistance helped Redbud get high tunnels for tomatoes and increase efficiency.

There are some government rebates and cost-share programs available to small farmers. North Carolina’s Small and Minority Farm Program offers assistance directly to farms with limited resources through outreach and education. It also offers cost-share programs for good agricultural practices, certification and water analysis.

Smith, for example, received two-thirds of the cost of high tunnels for Redbud Farm thanks to a grant issued by the Natural Resources Conservation Services. High tunnels are used as an irrigation system for crop production. This grant helped Smith make improvements to his farm to increase efficiency in growing tomatoes.

But cost-share programs generally require farmers to put up a significant portion of the money. Smith, for instance, provided a third of the cost of building high tunnels. Farmers who can't cover a portion of the costs are unable to install new equipment, which allows wealthier farms to grow much faster than smaller farms.

Universities share best practices; farmers spread the knowledge

Agricultural colleges and state universities throughout the U.S. have been offering supportive instructional programs for small farmers for hundreds of years.

North Carolina A&T was founded as a land-grant institution in 1890. The school was started on land made available by the federal government for the purpose of making farming accessible to the masses.

"There was a time in this country when most of the education in this country was for the rich and affluent people," Noble said. "Then there came a point where the government said, ‘For us to go forward, we’ve got to educate the masses.’ And so they designated some money and some land for each state to get 30,000 acres of land per congressman in Washington."

NC A&T has offered valuable resources to farmers since its early days. One of its primary programs today is demonstration farming.

Video Clip: Noble explains resources NC A&T offers to educate small farmers.

Small farmers meet with NC A&T instructors at demonstration farms to learn how to maximize the potential of their own land. As their farms improve and become exemplary, neighboring farmers can visit their farms and learn about best farming practices. This has allowed the practices taught by NC A&T to be shared across all 100 North Carolina counties.

"When people trained by us share with their neighbors, all of their results improve," Noble said. "We’re located in the middle of 100 counties. You can’t expect people outside of the neighboring three or four counties to take the time to come here."

While NC A&T tries to reach a larger target, it remains focused on supporting its surrounding communities through its three to four annual field day workshops. The workshops at its farm help relay information to the state’s farmers about how to become more profitable.

It doesn’t take more acreage to create more profits

Noble said some farmers have a misconception that land expansion will allow them to easily generate additional profits because they can increase production.

In reality, land expansion often creates deeper problems, he explained, because farmers may not know how to effectively harvest their new land and address new problems as they emerge. This ultimately sacrifices time and attention that could be better spent on existing land holdings.

"When it comes to volume, small farmers are normally at a disadvantage," Noble said. "A small farmer with limited acreage might try to work more land and then lose money. We work to show him how to get more money per unit and per commodity unit."

Government and farmers have a disconnect

Michael Shuman, an expert in economics and longtime supporter of the local food movement, helped President Barack Obama draft the Jobs Act in order to stimulate economic growth and increase jobs. But the Jobs Act has received significant opposition from the Republican Party. Shuman says the deep political division in Washington, D.C., has led to federal programs that are often ineffective at addressing small farming issues.

"State laws are going to be better and more effective than the federal laws because federal law allows long-distance relationships," Shuman said.

According to Noble, national politicians have become increasingly distanced from agriculture as America has become more urbanized.

"When our grandparents were around, a lot of people who were in the legislative branch actually had farm backgrounds," Noble said. "You had real farmers participating in making rules and regulations for farmers. In this country today about 1.5 percent of us are feeding 98.5 percent. We have farming rules mandated by people who aren’t farming.

"Their intuition may not be as great. Their understanding is not great. We face challenges because the people who are making decisions for farmers have no idea what farming is like. The disconnect is from the move away from rural areas and into cities."

Government actions carry significance

While most farmers argue there is too much government regulation, Gerald Dorsett, an environmental sciences professor at Elon University, says it is unfair to categorize regulation as a binary issue.

"A lot of government agencies would have a tendency to say there aren’t enough regulations," Dorsett said. "The typical farmer is going to tell you that there are. All regulations are not good and all regulations are not bad."

Video Clip: Dorsett examines the divide between farmers and government.

Redbud Farm underwent an extensive application process to become certified organic, but Smith and Joyner agree regulation of some form is necessary to establish uniform rules and establish reliable small-farm support programs.

"Because we are certified organic, we undergo an annual four-hour inspection to verify that we’re doing what we say we do," Smith said. "I appreciate that because it gives integrity to the term ‘organic.’ I don’t really have trouble with government regulations. If you’re doing the things you need to be doing, you’re not going to have problems with those."

Encouraging the public to buy local

The disconnect for farmers extends beyond the government.

Dorsett says one of the first questions he asks students in his community agriculture courses is, "What is farming?" and most people say a farmer’s primary role is caring for livestock. Many students enter his courses unaware of the struggles small farmers face and unaware of the impacts consumers’ behaviors have on agriculture and the people working in the industry.

Dorsett says one of the first questions he asks students in his community agriculture courses is, "What is farming?" and most people say a farmer’s primary role is caring for livestock. Many students enter his courses unaware of the struggles small farmers face and unaware of the impacts consumers’ behaviors have on agriculture and the people working in the industry.

"If we want to help out the small farmer, we need to become a much more educated society," Dorsett urged. "We have to go back to a philosophy that was strong here until the 1960s: buying local."

Employees at the Company Shops Market in Burlington work to provide healthy, fresh and local products to customers. The co-op opened in June 2011 with the hope of generating increased revenue for local vendors and changing consumer behaviors to encourage healthy practices.

Co-op faces stiff competition from discount stores and grocery chains

Company Shops has experienced steady growth since opening its doors, but its progress in competing against local grocery chains such as Harris Teeter, Lowes Foods and Food Lion and big discount stores such as Walmart and Costco has been gradual.

The Company Shops 2014 annual report noted a "drawdown on our cash while our current liabilities continue to increase slightly" and concluded: "Both of these trends need to be and can be reversed by increasing sales."

The co-op’s managers are aiming for additional owners and increased involvement from existing owners. The report noted a disappointing increase in owner spending from 2013 to 2014. In 2013, owner purchases increased $157,956 over 2012. In 2014, owner purchases increased by only $8,351 over 2013.

Megan Sharpe, community outreach coordinator for Company Shops, has relied heavily on social media to increase awareness. But she admits there are too many people the co-op has yet to reach.

"We have people living in the apartment building right down the street who still haven’t heard about us," Sharpe said. "We’re trying to do everything we can to increase awareness. We’ll blast social media and we’ll do emails, flyers and posters. It’s slowly getting out there."

While Sharpe looks to reach potential customers through visuals, interim general manager Ben Wright relies on interpersonal communication.

Wright and Sharpe argue it is virtually impossible to compete with fast food chains. McDonald’s Dollar Menu currently features a fruit and yogurt parfait, double cheeseburger and chicken nuggets along with much more, whereas the Company Shops deli menu features a variety of sandwiches starting around $8.

"People eat with their eyes and they eat with their wallet," Wright said. "It’s a matter of breaking down paradigms with folks and not having to sell them a product but sell them a new viewpoint and getting them to change completely."

Exploring trending markets is key to small farmer prosperity

Despite the slow progress for many co-op markets in acquiring new customers and in changing consumer behavior, the demand for fresh, organic local food is gaining momentum.

Consumer demand has grown by double-digits every year since the 1990s, and organic sales increased from $3.6 billion in 1997 to $39 billion in 2014, according to the Organic Trade Association.

Shuman authored “Going Local” to empower communities like Burlington to revitalize themselves and illustrate how consumers are willing to pay more for quality organic goods.

"People with limited incomes don’t understand the differences between price and value and frankly most people don’t understand this difference," he said. "Basically, no one buys anything simply on the basis of price. If that were true, Starbucks wouldn’t exist. People make their decisions on the basis of value, not just poor people."

Audience engagement is also essential for small farms to excel

Although it may be wise for farmers to grow organic goods, it is just as important for them to market their crops effectively.

Video Clip: Joyner explains how she interacts with her customers at farmers' markets.

At Redbud Farm, Nancy Joyner created an email list to garner support and enhance the farm's relationship with consumers. She also regularly updates a Facebook page to keep the farm's followers up to date with the latest crops being brought into farmers' markets.

"You can work as hard as you want to but you’ve got to have folks to buy your food," Joyner said. "You've got to pay attention to the relational aspect of getting to know the people."

Uncertain future remains

As small farms explore new markets and compete for consumer attention, an uncertain future remains.

The average age of farmers is increasing. The number of small farms is declining. Income inequality is rising. More and more people are moving away from rural areas. Government cost-share programs often require poor farmers to put up money they don’t have.

And despite all these issues, farms like Redbud remain optimistic and look to inspire a younger generation to enter an agriculture industry very much in limbo.

Growing emotional, Smith says, "We want to be an example for young people who think they might want to farm."