All Takeva Mitchell could think of was getting clean and showering — hoping to erase the feelings of disgust, guilt and pain sticking to her skin. When her roommate found her crying she encouraged her to call the Elon Town Police. It was March 13, 2014. She had been sexually assaulted.

Mitchell, who graduated from Elon University in 2016, was a sophomore at the time of the assault. She lived in the same apartment complex as Adrian McClendon, also a sophomore at the time. They were hanging out for the first time until things took an unexpected turn at around 11:45 p.m. She struggled to fight him off. All she could think about was that she could use her strength to escape the touching, groping and pushing.

“It wasn’t until he got real physical with me that I realized, ‘Oh this is about to happen,’” Mitchell said. “Anything I did, he was on me. He was on my every move.”

Eventually, Mitchell yelled for McClendon to stop and let her go. He stopped and shooed her away. She gathered her belongings. Before she could leave the apartment, he reached out and put his hands inside her pants. She broke away.

Daisy, a sophomore whose name has been changed to protect her identity, was walking home from a fraternity party when she texted a fellow student with whom she had sexual relations before. But they hadn’t had intercourse — she always made sure to communicate with her sexual partners that she wanted to wait for marriage. It was Sept. 3, 2016.

She went to his apartment and they started getting intimate. As they laid naked in his bed, he kept asking her how certain contact felt. She responded by saying that it was fine but warned him not to go further or he would be inside of her. At one point as she laid on top of him, she said he aggressively thrusted his hips and penetrated her, an unwelcome action.

“I hopped off and went to the bathroom and there was a lot of blood,” Daisy said. “That was the most terrifying part of it — I looked down and there was blood everywhere.”

About 20 percent of college women have experienced sexual assault, according to a 2015 Washington Post and Kaiser Family Foundation survey project. The same survey also shows how opinions about consent differ between men and women. Those surveyed stated that 89 percent have not been held responsible for the incident while 10 percent were.

“Yes, I had been drinking the night of my assault,” Daisy said. “Yes, I texted him first the night of my assault. Does that mean I wanted him to put his penis inside of me? No, I don’t think so.”

Reporting or remaining silent

When Mitchell reported her case on the night of her assault, she remembers her mind was going crazy. She did not know if the officers were going to believe her story or if they would take it seriously. After telling the officers who arrived at her apartment what had occurred, she was taken to the station to give an official statement.

“They want you to tell where you were standing when this happened and where was he standing and where was his dresser at and where was his TV at and where was his bed,” Mitchell said. “Still to this day, I can tell you exactly how his bedroom was lined up.”

Mitchell said the information she had to give in her statement had to be very precise, including the times and specific details of what exactly occurred. She said she understands why many victims do not report their cases. Going through the reporting process requires victims to constantly remind themselves of an experience they want to forget.

The 2015 Elon University Annual Safety and Fire report, the most recent report, states that there were three reported cases of rape and one of fondling. This is the same number of reported cases of rape and fondling in 2014, and two more than those reported in these areas in 2013. Because of the different avenues students have to report their cases, this is not a clear estimate, nor does it say that only four sexual assault reports occurred that year.

When Daisy walked home after her assault, she called Safeline, the university’s 24-hour confidential support hotline, which an advocate gave her as an option to report the case as well as if she wanted to go to the hospital to complete the rape kit. The morning after the assault, she went to the hospital to complete the rape kit which she said was almost as bad as her original experience.

“I had to tell the story about seven or eight times, which is a nightmare because it just happened,” Daisy said. “I had to relive it over and I cried every single time I told it.”

According to the Elon Department of Health Promotion, students who believe they have been victims of sexual assault can report the incident by contacting law enforcement, whether that be Campus Safety and Police, or Town of Elon Police. They could also contact Elon’s Office of Student Conduct, or Human Resources. They have the right to report in one or all of those avenues. They can also contact Safeline and keep it confidential through the coordinators for violence response or counseling services.

Before choosing to report, Daisy was contacted frequently by the Safeline responder to remind her of her options. Though he was her friend and she knew there would be social repercussions that would affect them if she decided to report, she chose to make her official statement on Sept. 16, 2016, through the Student Conduct.

“Every time I was going through the process and I was tired and sad and didn’t want to do it anymore, the responder said, ‘Why did you choose to press charges in the first place?’” Daisy said. “I didn’t want this happen to another girl. I can’t let this happen again.”

According to the National Sexual Assault Hotline, females between the ages of 18-24 who have been sexually assaulted do not report to law enforcement out of fear of reprisal, not wanting to get the perpetrator in trouble, the belief that the police will not do anything to help, the belief that it was not important enough to report and the belief that it was a personal matter. Most students surveyed said they did not report because of other reasons.

The U.S. Department of Justice special report on Rape and Sexual Assault Victimization Among College-Age Females, states approximately 80 percent of sexual assault victims knew their offender.

Stepping into the Reporting Process

Randall Williams, director of Student Conduct, says it is up to the student to decide if they want to report and press charges either through Student Conduct or campus police. Even if a student goes to Student Conduct to report, they are still reminded of resources available to them such as counseling or are advised to take the case to the police.

“Students have their choice,” Williams said. “You don’t force a student to report to us. We don’t force a student to go to the police.”

Both Mitchell and Daisy’s cases were carried through Student Conduct. This office investigates under the standards they follow. They take the information to their Title IX coordinator and share what they have found to the respondent and defendant.

Williams believes a lot of students choose to report through Student Conduct because this office uses a lower standard of proof in holding someone accountable than when reported to the police. Students also choose to report through Student Conduct because this civil system is more likely to find someone accountable for their actions and sanction them.

“We’re dealing with sanctions as it pertains to the university,” Williams said. “In a criminal process, it pertains to someone’s freedom.”

Under the Student Conduct investigation, both sides provide statements on what occurred the night of the assault along with statements of witnesses.

Daisy said her perpetrator was found not guilty of nonpenetrative sexual assault, but found responsible for nonconsensual sexual intercourse and penetration. She said he had a one-year suspension, which he appealed under procedural error and his sentence was reduced to six months.

Daisy’s case exceeded the 60-day time frame on decision making under the Department of Education school’s obligations under Title IX. Daisy said that it took about 90 days for the decision on her case to be made.

According to Williams, both parties in any reported case to Student Conduct receive the same information and reasoning behind the sentence is offered in the final report that the office offers to both.

“It’s very hard for me because I wanted him to be responsible for his actions,” Daisy said. “If he isn’t held responsible, then it can occur again without any repercussions and that’s problematic, but I also didn’t want to ruin his life.”

In Mitchell’s case, McClendon was charged by the state in March 2014 for sexual battery and false imprisonment by the Town of Elon Police. In a May 15, 2014, Alford plea — in which the defendant maintains innocence, but admits the state can convict — the sexual battery charge was dropped and the sentencing for false imprisonment was dropped for two years, according to Alamance County court documents.

Through Student Conduct, Mitchell’s case had a hearing to make the university’s decision regarding the case. McClendon was placed on preliminary suspension, a decision that frustrated Mitchell. She had asked the hearing board to suspend him for a semester.

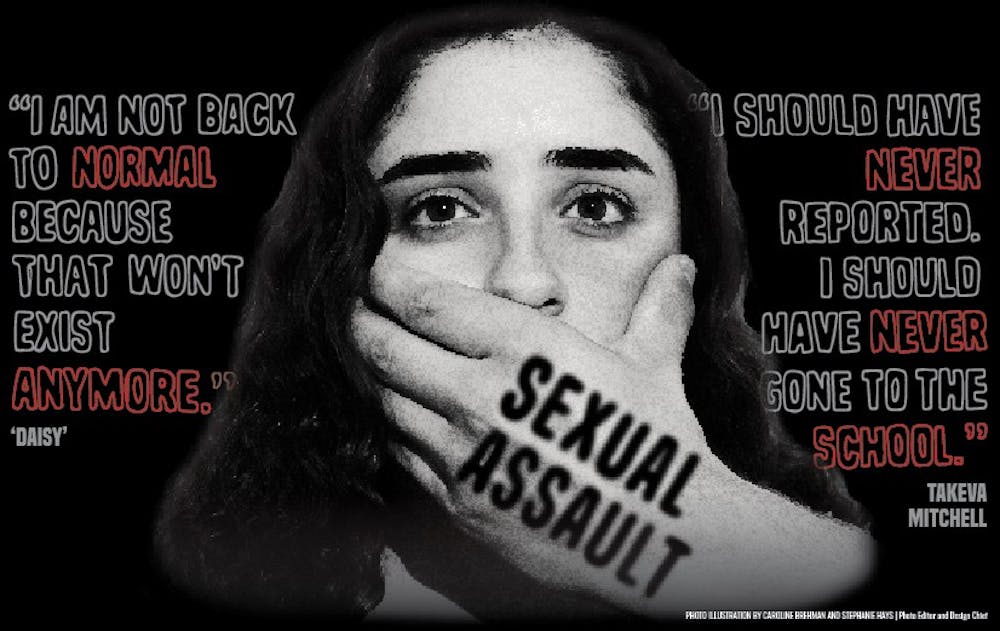

“I felt everything was a slap in the face, I should have never reported. I should have never gone to the school,” Mitchell said. “Because at the end, I took a loss. He didn’t take any. He got to stay on campus, he was still on the football team.”

Though McClendon admitted to sexually engaging with Mitchell, according to his arrest warrant, she did not understand why he did not get disciplined the way she had hoped.

“When is enough, enough?” Mitchell said. “What does a woman have to go through for justice to really be served when it comes down to sexual assault or rape?What are the qualifications for real justice for sexual assault and rape?”

Entering the healing process

Becca Bishopric Patterson, coordinator for health promotion, serves as an advocate for sexual assault survivors.

“There is no right or wrong or normal way to feel or heal after an assault,” Patterson said. “That’s going to look vastly different for many different people.”

The effects that come after the assault can affect a person’s physical, emotional and psychological aspects, according to the Joyful Heart Foundation. A person’s personal, social, professional and academic responsibilities can be affected as well.

“It is devastating for both parties,” Williams said. “You’re bound to see changes in behavior — some students become depressed, some students have high anxiety or stress.”

After the assault, Mitchell had a hard time sleeping and did not do well in classes. Though at some moments she wanted to leave Elon, she knew that if she had made that decision then she would know that her perpetrator would have won. That would have hurt her even more.

“I’ve done all the crying, the moping, the depression, the weight loss, the not eating,” Mitchell said. “I would sometimes pee on myself at night. I didn’t want to be around guys. I didn’t want anybody to touch me, to hug me.”

Seeing McClendon on campus made her uneasy, scared and nervous. Her support system along with her faith is what she believes helped her recover.

“I pushed through and I knew at some point through my faith I kept thinking, ‘God, I have been through a lot I know you can get me through this,’” Mitchell said.

Mitchell studied abroad in Australia the following spring after the assault. She refers to Australia as her “healing place.” There, she found peace and the ability to be comfortable with herself and around others. Though she has not spoken to McClendon since the time of the incident, she said she used to pray for him and for his healing as well.

“Life is so short, it is not worth being depressed and sad over one thing that happened in your life,” Mitchell said.

Daisy still has not told her parents. She has made a conscious decision not to and says it is “a cross she is willing to bear.” After the assault, she recalls having a difficult time being alone and reliving the experience. She went through withdrawal and had a lack of motivation. Despite having a cease contact order, which was issued by Student Conduct to prevent any communication with her perpetrator, there are aspects that she still recalls from him.

“It’s the small things that you don’t even think about,” Daisy said. “The way he talked, the way that he moved, you think you see him at the corner of your eye and it’s not him.”

The support from her friends as well as from the coordinators for violence response has helped her through this process. She considers herself on the path to recovery.

“I am not back to normal because that won’t exist anymore,” Daisy said. “This is part of something that happened and this is part of who I am now, but it’s not all of who I am.”

Defining sexual assault

For Mitchell, a simple definition would be any type of sexual contact or behavior that occurs without explicit consent.

She said a problem exists within the definition of sexual assault.

Elon’s 2016-2017 student handbook defines sexual assault in two categories- nonconsensual sexual contact and nonconsensual sexual intercourse. Sexual exploitation can also be linked to the definition.

Daisy defines sexual assault as an “unwanted or unwarranted sexual advance.” She acknowledges that people of all gender identities will have their own definition of this term since everyone’s views and experiences with sexual assault are different.

Though the definition of sexual assault not only varies between states but also between institutions, Leigh-Anne Royster, director of inclusive community development, said it is also an umbrella term that covers different offenses.

“I think that sexual violence is such a severe epidemic with severe consequences for such a huge proportion of our population,” Royster said. “We don’t even consider it to be the same kind of issues as other epidemics that cause detrimental effects for folks. It is critical because it is largely ignored by much of our population.”

When she began working at Elon 12 years ago, she said there had been maybe one or two incidents of sexual assault reported. Once she began working to improve and add resources that could assist victims with the reporting and healing processes, the numbers steadily increased to 32 the following year after she arrived.

The percentage of sexual assault is unclear on college campuses because of the divide that exists between reported and unreported cases. The National Sexual Violence Resource Center states more than 90 percent of sexual assault victims on college campuses do not report the assault.

Addressing society’s stigmas

Since there is no normal healing process, Patterson believes an aspect that consistently helps is that whomever the survivor confesses to the first time about the assault responds positively and is willing to help them. Then the survivor may seek other resources. If that person responds in a way that blames the victim, the number of those survivors that will speak out and seek help drastically declines.

Daisy believes that victim blaming makes society easily wrap their head around the subject of sexual assault.

“I blamed myself when my friends didn’t blame me,” Daisy said. “The whole culture of victim blaming is so innate to human nature in rationalizing these actions.”

Elon requires all incoming students to complete Haven-Understanding Sexual Assault, an online sexual assault prevention and education program, and offers skits during orientation, speakers and SPARKS sponsored events. Daisy believes that despite all of these efforts, work still needs to be done to raise awareness and create an environment where survivors feel comfortable reporting.

“We have to continue to change the narrative of what sexual assault looks like,” Williams said. “There’s got to be deeper conversations about consent and college culture.”

Patterson, who works closely with the educational aspect of sexual assault and other issues on campus, believes that the most powerful way to educate people is through peer-to-peer interactions. Through these interactions, people know how to respond and handle sexual assault incidents.

“The more student voices we have spreading the word all over campus, the better the culture is going to get,” Patterson said. “We’re all participating in this culture and we’re either participating or challenging it. We all have a responsibility in this.”