One Friday morning, a 15-year-old boy and his cousin walked out of prayer and began taking pictures of the life surrounding them. Before they knew it, Syrian mercenaries were accusing them of working for a foreign news agency. The next minute, they were tossed into the back of a pick-up truck and taken to military intelligence in Aleppo.

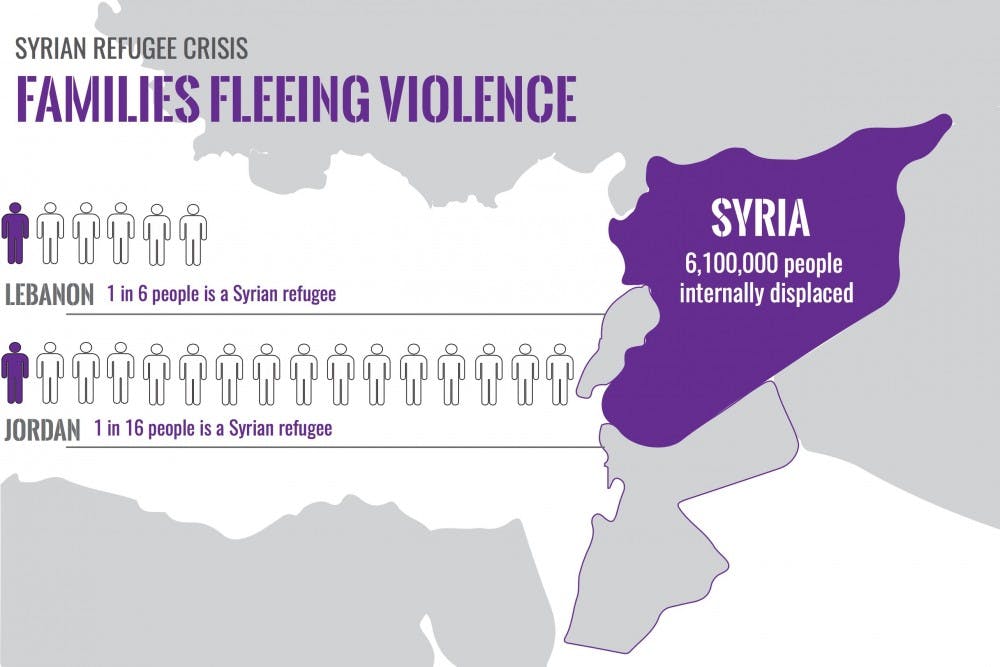

In 2011, the Syrian Civil War broke out. Some Syrians were forced out of their homes and into camps, some fled the country and others were kidnapped and conscripted. Since then, more than 11 million people have been displaced from their homes. Saria Samakie, a freshman at Georgetown University, was one of them.

Samakie was born in Canada, but moved back to Syria at age six when his grandmother passed away. The world around Samakie was quickly transforming, and with help from his dad, he changed as fast as his country did.

At age 10, Samakie learned how to drive so he could help his father work.

“Today, you are going to learn how to drive,” Samakie’s father said. “And every time you hit something, I will slap you once on the right side of your face.”

From then on, Samakie yearned to drive. Rolling into the desert, unbounded by any roads or rules, gave him a sense of freedom—a feeling he had yet to find anywhere else in his life. Soon after he learned to drive, however, the family lost their factory and farm to Assad’s forces and the rebels.

Five years later, everything in Syria was changing as the country descended into violence and chaos. On that Friday morning, when they were thrown into a cell at military intelligence, Samakie realized the danger he and his cousin were in. Samakie then extended his hand to his cousin and said, “It was great knowing you, but we’re probably going to die soon or never be let out of this place.”

After confiscating all their belongings, the boys were beaten, yelled at and interrogated. One guard told Samakie to tell him everything he knew or the guard would put him in a place where even God wouldn’t know where he was. At that moment, Samakie had a decision to make — to be weak or to show strength.

“Do you want me to tell you the truth or do you want me to tell you something that will make you happy,” Samakie said. “Because these two things are completely different.”

Samakie never thought much of his Canadian passport until that moment; the moment he was freed and reborn into society. Samakie was released after a religious leader came to vouch for him and showed his Canadian passport.

But only a month later, Samakie found himself sitting on a cold floor staring at a blank wall once again.

The Free Syrian Army, a Syrian opposition group focused on bringing down the government of Bashar al-Assad, kidnapped Samakie and demanded 2 million dollars from his family. Samakie knew there was no way his family could give the army that much money, so he told them they were going to have to kill him because he wouldn’t be able to pay that much.

That guard then left the cold, dark room and a different one entered, wearing an expression of pure disbelief.

“Are you crazy Saria?” the guard asked. “No, not really. Why?” Samakie said.

“The guy you just sat with beheaded nine people, and you were gonna be number 10, and you were there laughing,” the guard said.

“Yes, he beheaded nine people, but I still don’t see why I should be that afraid of him and afraid of telling him what I really think,” Samakie said. He believed he was likely going to die anyway and that a strong defiance would be his best defense.

Samakie’s kidnappers grew to admire him. After his family negotiated a ransom that they could manage to pay, his kidnappers saluted him as he climbed into his brother’s car.

Though Samakie had grown to respect his kidnappers, he would not dedicate his life to an ideology he did not believe in.

Defying his father’s determination to never leave Aleppo, Samakie eventually decided to leave Syria and make his way to Jordan with his mom, sister and niece. He found work, but always dreamed of going back to school. Samakie had not been to school since he was 14-years-old, when Assad’s forces seized his school in Aleppo for military use.

Through a friend, Samakie heard of a school that King Abdullah II had recently established— The King’s Academy in Madaba, Jordan.

Since Samakie had no remaining records of his schooling; he was an unusual applicant. Although King’s accepted Samakie, he failed the English entrance exam and could not afford the tuition with only 100 dollars in his pocket. Samakie’s tenacious resilience, however, showed its strength again, and he studied English on his own until he passed. Samakie then turned to crowdfunding to pay for his tuition. After only three days on Go Fund Me, he got a message from a man living in Amman. After talking to Samakie, that man paid for all three years of tuition in full, as long as Samakie promised the name of his donor would always remain anonymous. Samakie became an 18-year-old sophomore that fall.

Jack Blackwall, a close friend of Samakie’s from King’s, admires his fearlessness in all situations of his life.

Samakie’s dreams were not for the faint-hearted. His dreams required a hardworking and ambitious attitude that is unfazed by failure. Blackwall recounted a time when Samakie wished to be president.

“I think looking back he might think it was a silly thing to say,” Blackwall said. “But it provides a window into the scale of his ambition.”

Some of his close friends from King’s Academy agreed that they had never seen anyone work as hard as Samakie. Outside of school, he and two friends started a mobile classroom and went to refugee camps nearby to teach younger kids math and English. Their organization, Fikra 3al Mashi, continues to teach children today and are helping it grow and thrive.

After graduating from King’s, Samakie was awarded the Georgetown University Arrupe Scholarship. He describes his time there as if you gave Play-Doh to someone who has never touched it before—fun, colorful and moldable.

At age 15, Samakie was kidnapped and abused. Today, he is a 21-year-old freshman at a renowned U.S. university and has given speeches in both the U.S. and Europe about his story and the plight of Syrian refugees. He continues to advocate for Syrian refugees and is returning to Jordan this summer to grow the non-profit mobile classroom organization.

Samakie’s resilience radiates in every aspect of his life. He never gave into Assad’s military intelligence officers or his kidnappers, never became bitter about the loss of his family’s business and never raged about the violence all around him. When asked why he is not filled with resentment Samakie replied, “If I give in to resentment, then those bad forces would win, and I refuse to let them win.”

Samakie was faced with violence and heartbreak throughout most of his life, but he has never let that hold him back. He dreamt, learned and pushed past any obstacle until he achieved his goals. He pushed forward in a world filled with hate and war and came out on the other side with hope.

“If you have a dream, no one can stop you unless you stop yourself,” Samakie said.