Consent is sexy. The head nod, the squeeze of the hand, the wink. According to Elon University policy, these simple signs can't be interpreted as effective consent in the absence of a verbal, active "yes." But the charges assigned — or not assigned — to students accused of nonconsensual sexual acts don't always reflect what is mandated by university policy.

On Elon's Sexual and Relationship Violence Awareness and Response website, effective consent is defined as an active, verbal, uncoerced "yes" in the absence of substances such as alcohol and is required at each stage of sexual advancement.

Effective consent is clearly stated in the student handbook as a necessity for students to proceed physically in accordance with the Honor Code. But according to Whitney Gregory, director of Student Conduct, students don't always find it practical to pursue a verbal agreement to engage in sexual activity, and so verbal consent is not always the standard by which the outcome of cases is determined.

"If somebody is fingering someone and then it moves to oral sex and then it moves to intercourse, there may not be a 'Can I finger you?' 'Can I go down on you?' 'Can I put my penis in your vagina?'" she said. "I don't know of many students who have that conversation. Sure, it'd be great, ideally, but there's other ways, like body language, to gauge consent."

As director of Student Conduct, Gregory hears the cases of sexual assault that are reported to the university and said she has heard as many as five in one year, few in comparison to the number of cases that go unreported. Each case is so wildly different that she cannot provide a generic or average example for how fault is determined or charges assigned, but the university hearing system relies on the preponderance of evidence.

If personal accounts, witness statements and any other evidence shows it is more likely than not a student has perpetrated a nonconsensual act, he or she is held responsible. Both parties have the opportunity to appeal, such as if the charges are dropped or perceived to be too harsh.

As circumstances vary from case to case, Gregory said witnesses and every other ounce of available information is taken into consideration during the hearing process and there is no standard outcome or set of charges for types of violations. The consumption of alcohol, appearance of drunkenness or lack thereof, physical cues and whether consent was verbalized are just a few of the factors Gregory investigates.

"In my first meeting with the student, I'm going to talk with them and understand things and clarify things and help them understand that there's cases where they never said 'yes,' but everything else indicated consent," Gregory said. "But there are also cases where a student may have said 'yes, yes, yes, yes, yes,' but they were blacked out and they were clearly intoxicated and that's where I would say, even if you verbally said 'yes,' there were witnesses indicating you were slurring, you were stumbling. That's not consent."

Elizabeth Nelson, coordinator for violence prevention, said she has also found that students who go to her with their accounts of sexual violence or misconduct are not always practicing effective consent according to the university's definition. But the goal is for everyone to seek consent and affirm his or her own choices so they can better enjoy and understand their decisions to engage in sexual acts with others, she said.

"How consent plays out for individuals is not always going to be reflective of policy," Nelson said. "Policy is the way it should be happening, just like the other policies in place are the ways things should be happening. No one here lives in the fantasy world that everyone lives by policy, but that is the goal. The goal actually is to be giving clear and sober yeses."

But even in the absence of these 'yeses,' even when the university has information that effective consent by its own definition was not given, cases of nonconsensual sex have gone uncharged, according to Leigh-Anne Royster, director of Student Development.

Royster, former coordinator for personal health programs and community well-being, has heard countless students' accounts of sexual violence and assault and said she believes and practices that effective consent cannot be given in the absence of a verbal "yes," even if body language and lack of a verbal "no" indicate otherwise.

Royster said she has seen the university fail to consistently uphold this standard during her time at Elon.

"The Student Conduct process is not the same as a criminal justice process," she said. "I don't want to say they are the same thing, but as with any process like that where you're finding fault or guilt or finding any responsibility, you need to weigh the evidence on either side. I think that where I may view something as, 'Well, that person did not give effective consent,' I haven't always seen that result in the person who perpetrated that act being found responsible for nonconsensual sexual acts."

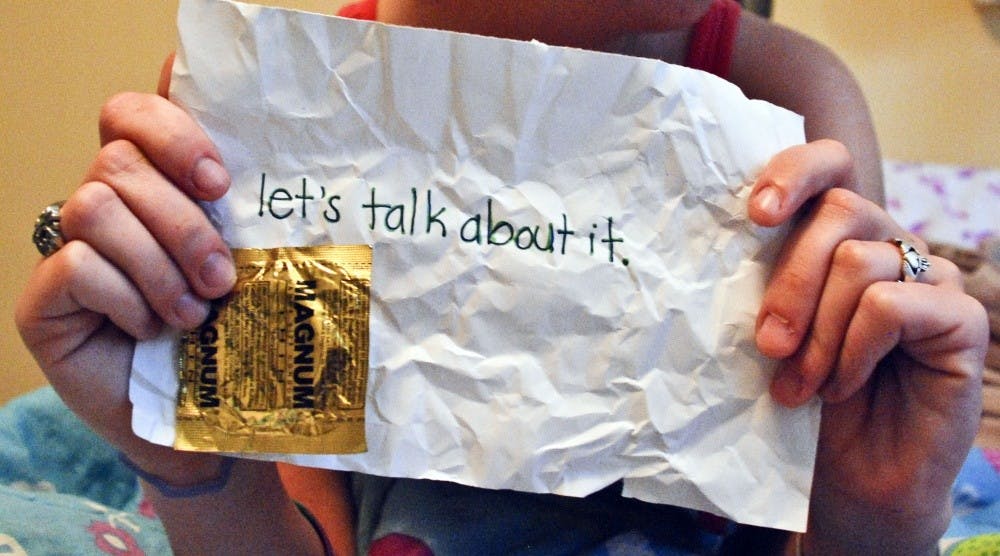

The discrepancies between Elon's enforced interpretations of what constitutes adequate consent for sexual progression reflects a broad, socially stigmatized misunderstanding of the importance of just talking about sex, Royster said. Many other faculty and staff members would probably be surprised by the definition of effective consent, she said, and likely don't practice it in their own relationships. But she is firm in her beliefs, and said she also doesn't think effective consent can be given between two individuals having met each other for the first time at a party — a potential stage-setter for regretted sex.

Even though most students likely don't ask before engaging physically with one another, and not every nonconsensual act is violent, actively seeking approval from one's partner can be an empowering way to prevent regretted sex and unknowingly being a perpetrator, according to Royster, Gregory and Nelson. Most reported cases are not simple incidents of students changing their minds about who they went to bed with the night before, but it's possible to lead an active, healthy and nonmonogamous sex life by taking the time to proactively make decisions about what one wants, Nelson said.

"It's a real misperception to think all these people are having sex and deciding the next day they didn't want to," she said. "That's inaccurate. Statistically, it's less than 2 percent. But what is happening, and I think this is important, is that lots of people are having sex they're not sure they want to be having and they don't feel good about it afterwards. And that, to me, is the power of consent."

Gregory said there are sometimes cases in which a lack of evidence prevents her from charging a student accused of being responsible for perpetrating a nonconsensual sexual act, but she never wants to undermine a student's path to recovery by assigning blame to a potential victim.

"No matter what's decided for a Student Conduct process or a criminal process, if someone feels hurt, taken advantage of, victimized, it's never healthy to say, 'Well, you're wrong,' from an advocate's standpoint," she said. "From the Student Conduct standpoint, I'm never going to say you're wrong. I may say I don't have information to support a violation of our policy, but not that you're wrong"