The darkly distorted passion project of producer-rapper/designer Kanye West dropped the same day as North Carolina MC J Cole’s standout sophomore LP Born Sinner and ever-evolving pop-frat weed rapper Mac Miller’s second major label release, Watching Movies with the Sound Off.

Cole and Miller delighted both fans and critics alike with cinematic production, an auteur-level attention to design detail and, most importantly to many young fans, official web streams of both of the albums in their entirety a full week before their releases.

Yeezus didn’t produce a single, wasn’t available for pre-order and doesn’t even have album art. The success of these young artists, still early in their careers, is commendable. But listening to these projects, you can’t help but hear a little old Kanye, a side of himself that Mr. West has seemingly left behind.

It is important to consider Yeezus in the context of the summer in hip-hop music, a scorching stretch of months that has included major releases by French Montana, Wale, Ace Hood and, most notably, the man that put Yeezy on in the first place, Jay Z (peep that Hova dropped the hyphen with the release of “Watch the Throne” in 2011).

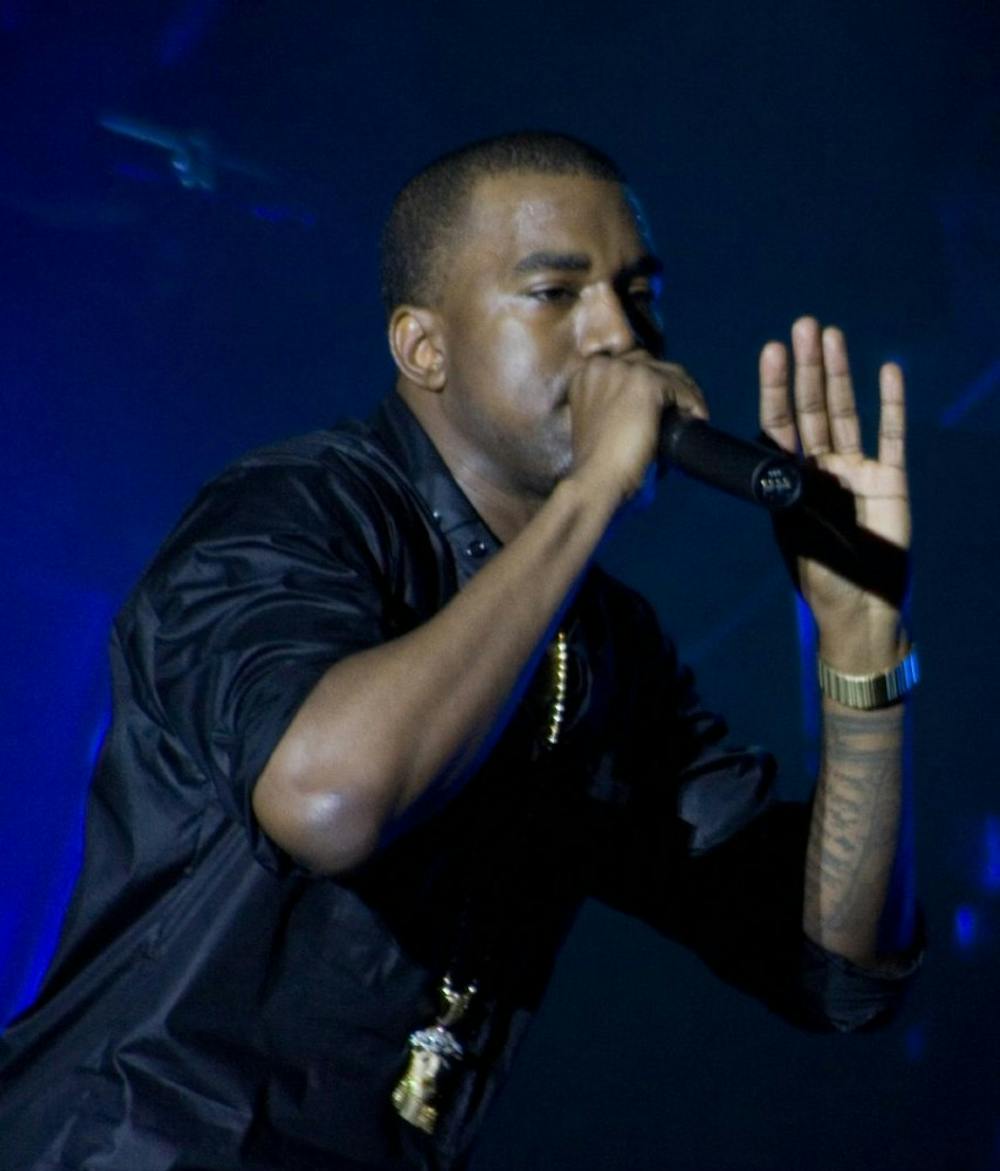

While Mr. Beyonce Knowles’ “Magna Carta Holy Grail” famously went platinum before its release with the #NewRules campaign, anchored by a status-quo shattering deal with Samsung valued at $5 million, Kanye West doesn’t care about album sales. He echoes this sentiment at every performance, in a ten-minute interlude he allots for himself. West shouts over a choreographed loop of the “Clique” instrumental, lambasting and expressing his disdain for seemingly everyone in “the industry” (music, media, fashion).

This idea was further reaffirmed by super-producer Timbaland, who asserted to BBC Radio One that Kanye does not even want to be mentioned in the same breath as other artists (save Michael Jackson, see “I am a God (feat. God)” track 3 on Yeezus). Kanye made his own lane; the entire industry bit that lane, so with the help of Rick Rubin, he built another.

Former punk rock producer-turned hip hop impresario Rick Rubin was brought in to salvage West’s original production, a messy, three-hour long indulgence lacking both the synthesized introspection of 808s and Heartbreaks and the poignant grandeur of My Beautiful Dark Twisted Fantasy.

Rubin encouraged a caustic, minimalistic sound for Yeezus, eliminating additional samples, vocals and six entire tracks. What emerged is a forceful, inaccessible, but ultimately visionary masterwork, something steeped in industrial punk and begging comparisons to Radiohead and Marilyn Manson, never Drake or Nas.

Yeezus defies comparison to almost any other major label release. The album is instead a sort of precise noise. There is unexpected structure, intentionally off-beat delivery, ratcheted up distortion and auto-tuned vocals. Track 2, “Black Skinhead,” is built around the demonic barks of mythical Hades watchdog Cerberus, punctuated by the visuals debuted on “Saturday Night Live.”

West has asserted himself as more of a visual artist than a sonic artist, and here, in the most defiant track on the album, West embodies the persona of the angry Chicagoan. Here a rapper never defined by his social consciousness, while never escaping his self-consciousness, finds solace in it.

The largely electronic album is steeped in soul, contributing to a brokenness that comes to life in the low-resolution production. There is intention in every skipped beat, modulated vocal or distorted 808. But none of this equates to lo-fi. This is designer-quality music. When West produces music he takes the same tactic as Louis Vuitton, who burns unsold handbags at the end of the season. There are a lot of ideas that we will never get to hear, making what is left so valuable.

[quote] Yeezus defies comparison to almost any other major label release. The album is instead a sort of precise noise."[/quote]

West was never a singular artist, and music is not a singular pursuit, but inexplicably absent from the record are any of Kanye’s robust stable of GOOD Music artists. Instead, un-credited guest verses are rawly delivered by largely unproven MCs Chief Keef, King L and Assassin. The features offer another layer of distortion on West’s message, yet add an undeniable clarity and energy to the tracks “Hold My Liquor,” “Send It Up” and “I’m In It” respectively. The only credited feature is, of course, God. West refuses to use his album as a platform, foregoing the boost in exposure credited features would offer Pusha T or Big Sean, who both have major projects expected in the coming months, for a commitment to his vision of an extension of the hip-hop industry.

West is undoubtedly a polarizing character, as he was barely in the same country as newly minted baby-mama Kim Kardashian for the length of her pregnancy while he focused on the album. Their child together, North (Nori) West, whose birth almost coincided with the album’s release, is not mentioned on the album. But here West reminds us of why we fell in love with him in the first place, with pitch-perfect sampling, drums and powerful lyricism most prevalent on the conscious, six-minute cut “Blood on the Leaves” and album closer (my personal favorite track on the record) “Bound 2.”

Yeezus is the defiant, extravagant and provocative work of a tortured genius, and the greatest departure for an artist who seeks to reinvent possibilities for himself and his industry with each release. We are lucky to be along for the ride. There is much more GOOD music to come.