Dr. Ahmed Fadaam, previously a local reporter in Baghdad, knows what a war zone looks like.

“I'm leaving the house and there's a huge explosion that happened just a few blocks from where I live, and it's a car bomb,” he said, describing a specific day. “I drive there and there are tens of bodies fully burned and there are tens of wounded people and burnt cars everywhere – it's a daily scene.”

While most people’s instincts tell them to run away, a war reporter’s instincts tell them to stay, take photos, count bodies and capture the scene.

There’s an endless supply of war and conflict all over the globe and war reporters are there throughout the entire process, doing what they can to ensure the world hears all sides of the story and can see past propaganda.

War reporters witness these gruesome sights on a daily basis. The task is high-risk and high-stress, loaded with personal sacrifice. So what keeps a war journalist going back to these hard places?

Los Angeles Times war correspondent David Zucchino said, for him, it’s the story.

“The reason I got into journalism was to put myself at the center of events, particularly with overseas reporting,” said Zucchino. “You're basically covering history [and] historic events unfolding before your very eyes, and it’s just exhilarating to be there in the middle of it as it’s happening – doing that on the ground, original, sort of first draft of history.”

Fadaam said the curiosity he developed when he started working as a reporter got into his blood and he couldn’t get rid of it.

“You keep trying to know what’s going on around you all the time even if you’re not working, if you're not reporting,” Fadaam said. “It becomes like a habit inside.”

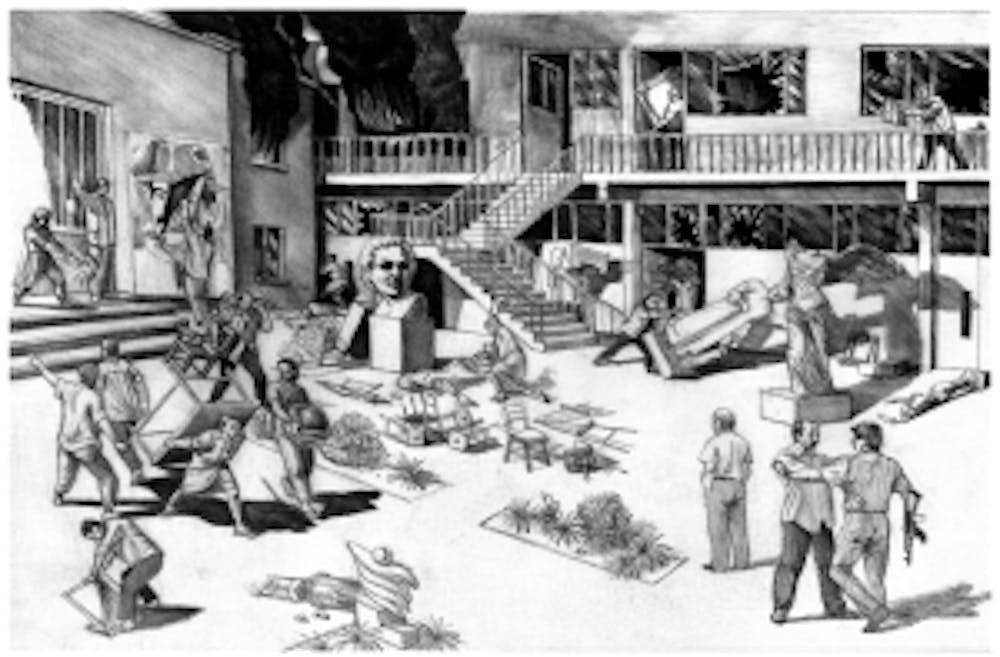

As an Iraqi native, Fadaam lived in Baghdad and taught art until the war began in 2003 and his studio was looted and burned. He soon took a job as an interpreter for foreign journalists, and then became a local reporter for several media agencies. Two year ago, he took a full-time job teaching at Elon University’s School of Communications and moved his family to Burlington, N.C.

Zucchino is clearly addicted to the excitement of war reporting, as he has been a war journalist since 1982, covering 30 countries, including Afghanistan, Libya and Egypt.

“There is an adrenaline rush, particularly in combat, where you’re kind of jacked up all the time, and you’re running on a high level of energy and everything is happening fast and is very important and you’re just so focused,” Zucchino said.

Fadaam agreed, adding that war reporting can be like an addiction to trouble.

“You can hear the sounds of war surround you, like the explosions, the gunfire and everything,” Fadaam said. “Every minute, every second you spend there is full of rush and adrenaline. You reach the point where you start to like it. You get addicted to it. That’s why I think they call the journalism profession as ‘looking for trouble’ profession.”

But even a journalist high off the rush of war reaches a breaking point.

“That’s the thing about war zones,” said Dahr Jamail, a war reporter for Al Jazeera English. “They’re so dehumanizing by nature because for one human to kill another, you have to dehumanize him, and when that’s happening on a daily basis in these streets where you are, you can’t not be affected by that. As a journalist, you come out of that situation you have to figure out, ‘Okay, what do I need to do to re-humanize myself and kind of get back down to the basics?’”

Fadaam still describes himself as an artist, even though he said spending so much time in a war zone has hardened him.

“You start to feel you’ve lost part of your humanity,” he said. “I used to be an artist, someone who thought himself as a soft, gentle guy who appreciates beauty and everything and uses art as a sort of language to communicate with people to make them know what he feels or what he’s thinking. I couldn’t stand the sight of blood, I couldn’t see someone crying, I couldn’t see someone injured or feeling any kind of pain. But after a while all this was gone. I can spend 10, 15 minutes trying to find a good picture of a fully burned dead body in the street with lots of blood and human parts all over the place and don’t feel a thing.”

Zucchino and Jamail said their experiences are similar to those of soldiers, especially the effects of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), which followed them home.

War journalist Sharon Schmickle wrote in “Reporting War,” a short handbook discussing PTSD, that journalists and soldiers are both exposed to combat stress, and news organizations should provide response options, as the military has begun to do.

“The primary thing was you just become numb because you’re in this intense situation, and I think what I’ve learned about PTSD is to psychologically cope with it, you just start shutting down all feelings,” Jamail said. “The only thing you can really feel is rage.”

“The primary thing was you just become numb because you’re in this intense situation, and I think what I’ve learned about PTSD is to psychologically cope with it, you just start shutting down all feelings,” Jamail said. “The only thing you can really feel is rage.”

Jamail said other symptoms of PTSD, like insomnia, nightmares and an inability to fit back into regular society, are troublesome. The situation in Iraq became normal to him, meaning the patterns of home now felt abnormal.

“You just don’t feel like you belong,” Jamail said.

Each journalist finds his or her own way to deal with the PTSD and begin the healing process, enabling them to return to places of conflict. Jamail said he is now more mentally prepared to go on assignment because he knows to put his “emotional armor” on, and that it takes him a few weeks to remove it when he’s back home.

Zucchino waits until he gets home to process what he’s seen.

“I put it aside at the time you’re under stress, one for danger and one for deadline pressure, because you have to get the story,” he said. “When awful things happen and you see terrible things, I just kind of compartmentalize because you have the job to do and if you start getting emotional, getting upset, you’d be helpless and you couldn’t do your job. When I get back, then I start thinking about it, then I get upset and emotional about it.”

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rWxwofhORWM

The art of journalism has provided Fadaam a way to help cope with his hardened feelings and “steam out the darkness,” he said.

“Sometimes I dig out some of the old videos and photographs that I’ve done in Iraq and just watch them and try to remember what it felt like back then,” he said. “Why do I feel so sad right now? Why didn’t I feel like this when I was in the spot taking these pictures? What changed? Is it because I’m living far away from that spot right now? Is it because it’s been a long time since I took this picture and something has changed inside? Something is healing inside me? What is it? But in any case, you feel good because you feel like you’re coming back to your human nature. You haven’t lost it.”

Taking a vacation or doing relaxing activities seem to help relieve stress as well.

“My wife and I like to go to music events, go to concerts,” said Zucchino, a North Carolina native. “We do art festivals. We just try to get out and relax. Go to Asheville or go to the beach.”

Jamail said he prefers to take a holiday somewhere — ideally in nature — in order to unplug from a trip.

“That’s just how I personally recalibrate myself with whatever’s going on in my life,” he said.

Jamail also found getting a dog was one of the most helpful recovery tactics. He said the military has embraced this method and trained dogs to place with soldiers suffering from PTSD.

“Pets know our mood all the time,” he said. “If you’re sad, the dog will just come up and lay near you and that kind of thing. That’s actually really what helped the most.”

While training and recovery assistance programs may vary between media outlets, the University of Washington has a program specifically for war journalists. The Dart Center for Journalism and Trauma, located in Seattle, offers training, fellowships and advocacy for war journalists.

Reporters Without Borders also provides services for war journalists.

The decision to return to a war zone is a personal one. For Fadaam, his choice is between his safe new home and returning to his profession in his homeland.

“Do you prefer being there, where it’s dangerous and there are no services or anything? Or do you want to stay here where it’s nice and beautiful?” he said. “Why do you have these feelings inside you that whenever something bad happens in Baghdad or other places in Iraq, whenever you hear about people that are killed, why do you feel so bad? Why do you feel so sad? Why do you feel this urgency inside you that you want to be there? You have to fight it if you want to stay here. Or you just have to give up and go back. You choose.”

In October 2013, Zucchino returned to Afghanistan for his eighteenth trip since 2001. He wanted to return to Syria, currently one of the most dangerous countries in the world.

Why? To tell the story.

“An important story,” Zucchino said. “Understanding it, and helping other people understand what’s happening on the ground, because in a place like Syria, it’s really hard to get firsthand reports because it’s so dangerous.”

Jamail, based in Qatar, struggles between his mental state and the responsibility he feels to go and be a voice to the voiceless.

“It’s a constant tug-of-war,” he said. “I can’t say that I’ve reached a resolution with it.”