Let’s start large-scale. The United States is the world’s leader in incarceration, locking up an average of 716 per 100,000 people. Now, let’s look at North Carolina. The 2012 census tallies an estimated 9,752,073 people living in the state. Alamance County houses 153,920 of that 9 million.

Bearing in mind the statistics, between 800 and 900 people are incarcerated in the Alamance County jail located in Graham, N.C. (taking into account children under the age of 10). These men and women are imprisoned for a variety of reasons, but upon their exit are all deemed “untouchables” because of past fallacies.

Rarely do these men and women get their second chance in the economy and, ultimately, society. Rather than have to coax local business owners into giving ex-offenders third shift jobs at the mill, organizations are realizing the community needs to proactively re-integrate them back into jobs, their families and rehabilitated lives.

Programs around the Winston-Salem and Alamance areas have recognized the need to tackle the re-entry issue as unemployment spreads because of blemishes on records.

Sustainable Alamance has a small-scale feel but a large impact on the surrounding community. Based in Burlington, N.C., it provides for the community by including underutilized human resources, most often former offenders, whom have experienced exclusion from participating in the local economy.

Project Re-entry, based in Winston-Salem, N.C., also assists former offenders, but through very different methods. Provided by the Criminal Justice Department staff, the project starts inside North Carolina prisons and continues on to guidance out in the community to promote a healthy reintegration.

Jobs not only give ex-offenders responsibilities but also keep them out of jail, in more ways than one.

There are several potential fees ex-offenders have to deal with, and providing simple services isn’t going to solve those problems. Most exit prison with probation or restitution fines, owe child support or have to pay off dues from their court-appointed attorneys and jail time. The probation fee in the state of North Carolina is $40 per month. Failure to pay, due to discrimination in the work place, could result in recidivism – a return to jail.

The average annual cost of incarceration in North Carolina is $29,965 per inmate. Costs can reach $32,000 depending on the level of security. That’s money out of the taxpayer’s wallet. Those on probation who aren’t able to pay the yearly fee of $480 will get put back in jail, resulting in the $27,000 fee for taxpayers to fund that single sentence. From the economy side of things, it doesn’t seem like a very efficient plan.

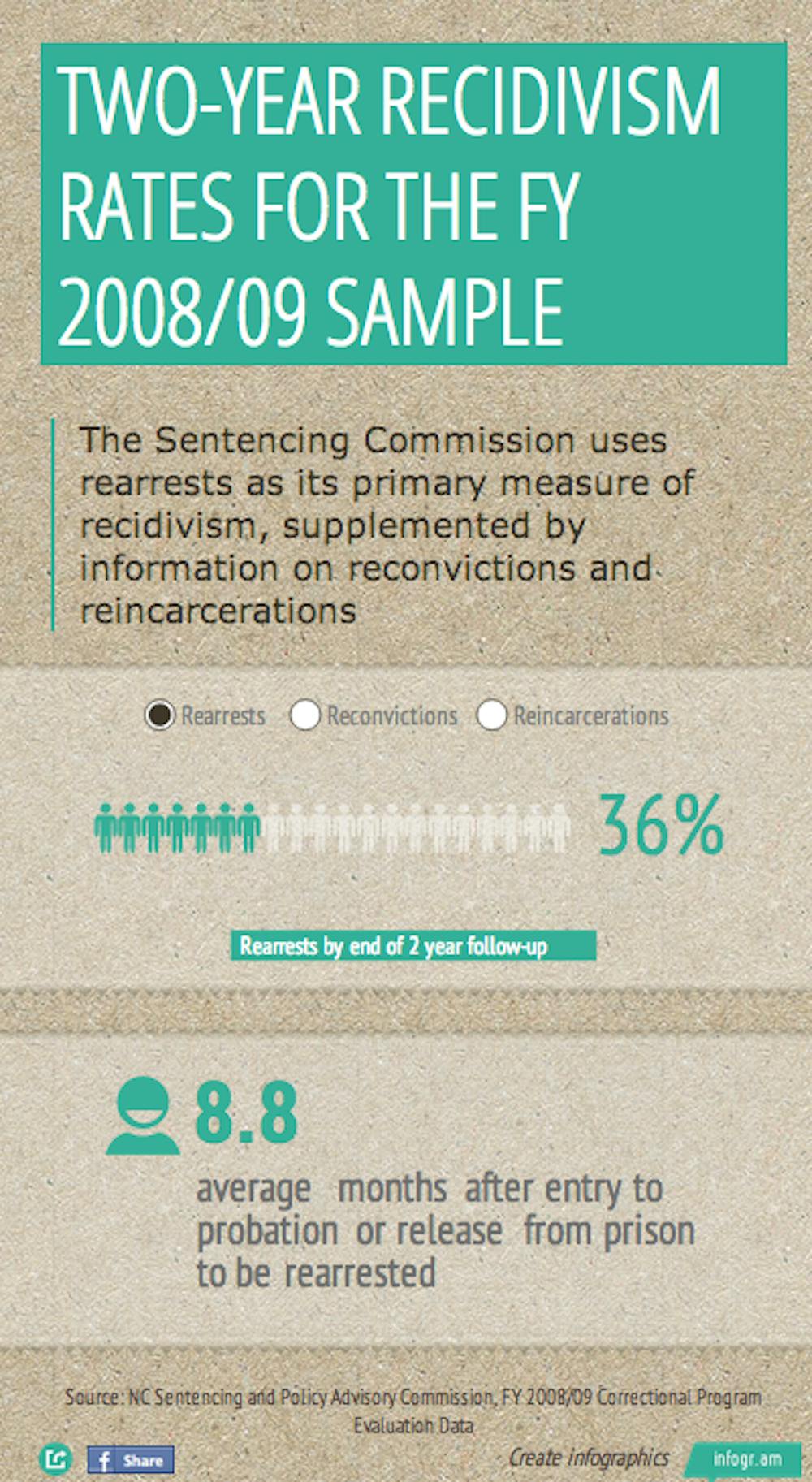

In 1998, the North Carolina General Assembly directed the Sentencing and Policy Advisory Commission to prepare biennial reports evaluating the effectiveness of the state’s correctional programs. A study released in fiscal year 2008/09 analyzed a sample of 61,646 offenders released from prison or placed on probation using a two-year follow-up period.

The study defines recidivism as arrest, conviction and incarceration during the follow-up period.

Of the sample, 23.9 percent were rearrested during the one-year follow up and 36 percent were rearrested during the two-year follow up. By the end of the two-year follow up, the 2008/09 sample accounted for 40,152 rearrests.

Overall, 24.1 percent faced incarceration for a second time.

“It’s not a just system, I had to do something,” said Phil Bowers, who left a six-figure salary in chemistry to start Sustainable Alamance, a ministry that helps ex-convicts in the area assimilate into society.

Sustainability doesn’t always mean solar panels and windmills. It also means using the human resource. Since Alamance County doesn’t have the resources to give people jobs, Sustainable Alamance creates jobs to help ex-offenders take on responsibilities and pay off their dues.

The Urban Farm project teaches ex-offenders how to grow and maintain organic, healthy produce while becoming engaged in the new economy and local food. Offenders go from victimizing their community to building it back up for the better.

Workers spend their days tilling and planting on the half-acre of land. In the summers they nurture tomatoes, okra, squash, cucumbers and melons; in the fall – turnips, beets, broccoli, cabbage and lettuce.

“If a guy comes up and needs money to pay his child support, I’ll tell him to come out and I’ll give him money if he earns it,” said Bowers.

He encourages ex-offenders to become economically sustainable not just as means for temporary relief, but for future development.

For those who become very interested in the farming, Alamance Community College will give them a full scholarship in horticulture, a momentous opportunity as an alternative to recidivism.

This is not a community garden; it is a money-making proposition for those who are discriminated from the workplace. The project currently sells their produce to Company Shops Market in downtown Burlington. The ideal plan would be to sell all of their produce in the surrounding neighborhoods, to the people who need healthy, local food.

However, much of the population in the surrounding area uses food stamps to buy food. Bowers has been petitioning to get certified to take Electronic Benefits Transfer (EBT) cards to get his food in the hands of the people that need it, while also being able to make money for the workers.

But Bowers also has his sights set on the horizon. He plans to grow into a small business to provide more jobs for more people who need money. With access to five acres of land, there is plenty of space to expand.

An architect from North Carolina State University has drawn up a plan for future development, recommending models for greenhouses, crop placement and a local meeting place. Bowers is working on finding grant money to demolish the deteriorated warehouses on the plot of land and build greenhouses to establish themselves as a year-round nursery.

As a man who has sacrificed a lot to help others, Bowers has many problems with charity. Loaves & Fishes, a local independent food ministry headquartered in Burlington, provides groceries for hungry families. The organization recently closed due to lack of financial contributions after 14 years of service in Alamance Country. This kind of charity, Bowers said, is the problem.

“We’re stuck in this mindset that the poor are incapable of helping themselves, which is nonsense,” Bowers said. “We have guys coming through our program that were earning 300 grand a year selling cocaine. They are quite capable of taking care of themselves if you only send them down the right direction.”

Handcuffing people to depend on charity rather than to depend on themselves isn’t solving the deep-rooted issue, Bowers said. It’s only emergency relief for a chronic problem.

The Urban Farm project takes the opposite approach. Sustainable Alamance believes poverty is not a lack of money, but a lack of resources. It gives the power to the people that need it so they can help themselves. It provides ex-offenders with the resources and education to make their self-earned income.

“It teaches people that food doesn’t come from Loaves & Fishes,” Bowers said. “This is ultimately where food comes from.”

Those that work for all of the day labor programs available at Sustainable Alamance average daily incomes well above minimum wage. Bowers does his best to teach ex-offenders that they are as valuable as what the market will pay.

Typical entry-level positions in the workplace earn $7.25 an hour, while workers on the farm project make around $10 or more. The wages are the program’s way of encouraging ex-offenders to not always see themselves at the bottom. A dedicated summer worker has the potential to earn a couple thousand dollars in a few months.

“What we found is not just about a job, but a head and heart change as well,” Bowers said.

One of the major factors of recidivism released in a study by Brigham Young University was not only employment but also family support and a personal motivation to change.

Sustainable Alamance’s efforts to raise their pay above minimum wage gives ex-offenders a sense of pride in success, which positively correlates to lower recidivism rates.

Sustainable Alamance has placed 38 people into full-time employment. Of those 38, 25 would have gone back to prison based on the normal rate of recidivism (67 percent), saving the taxpayer thousands of dollars.

“Lots of people are willing to help ex-offenders,” Bowers said. “Right now, we’re the most integrated in Alamance.”

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=U3cMtgQW7TE#t=35

Smaller communities rarely have re-entry programs such as Bowers’. Bigger cities, where there are more numbers facing reintegration, have their own programs to deal with the problem.

With pre-release services available in 14 North Carolina state prison facilities and post-release services offered in 22 counties of the central, piedmont and western regions, Project Re-entry is a well-integrated and widespread system dedicated to finding jobs for former offenders.

Pre-release group sessions focus on cognitive thinking skills, coping with societal changes and rebuilding family relationships. A BYU study stated that individuals who have been previously incarcerated first develop an openness to change when they begin to conceive of personal change as a possibility.

Many of the attitudes and skills learned while incarcerated are not helpful for adjusting to life outside of prison, so helping the offenders move toward change, making them see themselves in a different light and giving them a sense of hope is what will alleviate some of the challenges associated with transitioning into the community. All of these things are tackled by the pre-release programming.

Rebecca Sauter, co-founder and coordinator of Project Re-entry, said the program’s philosophy and methods are common sense.

“It’s based on reality and honesty and is entrenched in passion,” she said.

Once released from prison, those who have successfully completed the pre-release program are eligible to receive services on the outside. Several factors affecting reintegration, according to the BYU study, include a return to substance abuse, lack of employment, low family bonds and low motivation.

Project Re-entry focuses on individual case management, so those who want to receive more services for the program are provided with personal and vocational support as the participants adapt to life after prison.

Services can last a year after release and even longer based on an individual’s needs, abilities and priorities. Post-release programming primarily handles employment training and job search assistance and eventually getting participants to work toward self-sufficiency.

“Just being available for them to talk to, a familiar face with whom they have established a supportive bond has proven to be extremely important to our participants, sometimes more than traditional service delivery,” Sauter said.

The program encourages offenders to own up to their responsibilities, take charge of their life and be rid of the “pity party” mentality.

All Project Re-entry staff hold Certified Business Intermediary (CBI) designations, meaning they have proven professional excellence through verified education as well as exemplary commitment to the business industry. The staff members incorporate standard CBI principles throughout the program’s courses to better prepare program participants for employment opportunities.

“Our participants’ confidence levels have begun to soar, because they know that there is hope on the other side of the wall,” Sauter said. “I think one of the main non-tangible items that we give participants is hope.”

As the only pre- to post-release re-entry program in North Carolina, Project Re-entry has seen measurable success through the years. The recidivism rate of members going through their program is down to 12.8 percent, a far cry from the general 24.1 percent rate studied by the Sentencing and Policy Advisory Commission in 2008/09.

Living with a criminal record is not the end of one’s life but the beginning that they chose. The facilities have always experienced demand from inside of the prisons, but now the community is looking at re-entry as something that is needed.

A community effort to erase the stigma of former offenders for a fair second chance in the community and economy, with the help of these programs, is the quickest way to end the recurring problem of release and recidivism.