If you are one of the students who made the President’s and Dean’s Lists over Winter Break, don’t celebrate just yet.

The President’s List consisted of 718 students who received straight A’s, and 1,256 students received no grade lower than a B- in a minimum of 12 semester hours while maintaining a 3.5 GPA, landing them on the Dean’s List. Combine those numbers, and you’ll realize more than 35 percent of students are making either the President’s or Dean’s List — that’s more than one-third of the student body. According to Elon University’s student handbook, the Dean’s Lists exists to “encourage and recognize excellence in academic work.” But with so many students making high grades, is the distinction still an honor?

This isn’t the first time Elon has encountered this issue. In 2008, Elon reported a shocking statistic: more than 40 percent of the grades students received were A’s. The number of A’s had been slowly increasing over the years, but passing the 40 percent mark warranted some administrative concern.

President Lambert quickly responded in a letter titled, “Who is an ‘A’ student today?” saying, “Clearly, we must remain committed to maintaining standards of excellence.” Six years later, the percentage of A’s has only gone up.

Elon’s student handbook outlines grades as follows: an A indicates a distinguished performance, a B an above-average performance  and a C an average performance. This fall, 45 percent of the grades given out were A’s, a 5 percent increase since President Lambert’s letter. Based on the handbook’s standards, those grades would indicate that almost half of Elon’s students have demonstrated a distinguished performance in class, and only 9 percent can be considered average (9 percent of grades given out were C’s). This overwhelming and increasing amount of academic success has led many students, faculty and staff to question the extent of grade inflation at Elon.

and a C an average performance. This fall, 45 percent of the grades given out were A’s, a 5 percent increase since President Lambert’s letter. Based on the handbook’s standards, those grades would indicate that almost half of Elon’s students have demonstrated a distinguished performance in class, and only 9 percent can be considered average (9 percent of grades given out were C’s). This overwhelming and increasing amount of academic success has led many students, faculty and staff to question the extent of grade inflation at Elon.

Grade inflation occurs when grades go up despite student performance not improving. The value of a letter grade decreases, and higher grades become less challenging to attain.

The problem

According to the Elon student handbook, “an Elon student’s highest purpose is Academic Citizenship: giving first attention to learning and reflection, developing intellectually, connecting knowledge and experiences and upholding Elon’s honor codes.” But is the university doing enough to challenge its students, especially now that most students are considered above-average? Sophomore Maggie Liston doesn’t think so.

Liston, a French and international studies double major minoring in political science, believes that academic rigor is lacking at Elon.

“I currently have a 4.0, and I don’t think I deserve it,” she said. “And, for me, I feel guilty, because I know that sometimes I’m not putting forth my best work, but it doesn’t influence my grades at all.”

During her first semester at Elon, Liston was shocked to discover her college courses were not as challenging as those she took in high school. She even requested outside coursework from her adviser in an attempt to push herself academically where her classes were not.

“I just had these expectations coming from high school that college would be this fountain of knowledge that I could soak up and that everyone would be as excited as I was, and it wasn’t that way,” Liston said. “So that upset me, and I definitely wondered if I was in the right place.”

Liston is not alone. Junior Delaney McHugo also sees a problem with grades at Elon.

“I think that a lot of the caliber of work that students do here is not necessarily matching up to the standards of grades,” she said. “Yet professors feel obligated to give students those grades for various reasons.”

The university has made efforts to combat grade inflation. One of the school’s mottos is “Engaged Learning,” which aims to expand a  student’s knowledge outside the classroom. Students are studying abroad, listening to guest speakers and engaging in extracurricular activities. Even with these initiatives, students like Liston don’t think that makes up for the lack of academic rigor.

student’s knowledge outside the classroom. Students are studying abroad, listening to guest speakers and engaging in extracurricular activities. Even with these initiatives, students like Liston don’t think that makes up for the lack of academic rigor.

“I think Elon has made significant strides, and I don’t want to discredit them, but my high school was harder than what I’m doing now,” Liston said.

Dr. Steven House, Provost and Vice President for Academic Affairs, recognizes the abnormally high amount of A’s and is concerned.

“[The high number of A’s] does a disservice to the ones that really, truly do have a distinguished performance,” he said. “They are trying to set themselves apart to be the ones to go to graduate school.”

Why?

One of the possible reasons for grade inflation is that professors purposely inflate grades to boost their performance on student evaluations, and Dr. House recognizes this as a possibility.

“I do believe that there is a perception with faculty that if I grade easier I will get a better student evaluation,” he said. “But I know that that is not always the case because some of our toughest graders are our most highest-rated faculty.”

Yet, the university’s toughest graders are definitely in the minority, especially with more than 70 percent of the grades falling between the A and B range.

Business professor Scott Buechler believes one reason for grade inflation is actually smarter students.

“Academic rigor I think has gone up, but I also think that the quality of students has outpaced the increase in academic rigor,” he said.

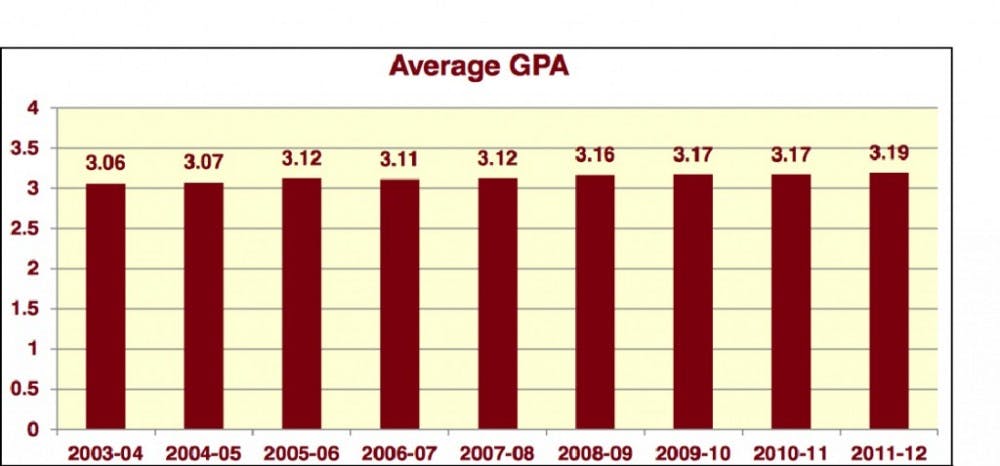

There is no doubt that Elon’s academic reputation has increased. In 2005, the average GPA for an incoming freshman was 3.72. Today, the average GPA for an incoming freshman is a 3.9. Perhaps the curriculum has not adjusted enough to the improved quality of students.

Nonetheless, McHugo believes the university will be hesitant to adjust the curriculum.

“It’s something we are kind of sweeping under the rug to kind of keep our overall image of having this intellectual climate, because people are getting good grades, and people are doing well in their classes, and that looks great,” she said.

How can we fix it?

Grade inflation isn’t a problem only at Elon. It’s an issue on a national scale. A recent Teachers College Record study shows that across a range of 200 universities, more than 40 percent of all grades awarded were in the A range. For Elon to address its grade inflation issue, it would require cooperation from the administration, teachers and students. The administration would need to enforce stricter grading standards, teachers would need to ensure the grade fits the standard, and students would need to do more than the bare minimum.

“I just think that we do whatever we can to pass by, and we’re paying thousands of dollars to go to this institution so it can challenge us academically first and foremost,” McHugo said.

The administration isn’t opposed to changing the system, but students need to come forward if there is a problem.

“I wish students would, in their student perceptions of teaching, indicate that they are unhappy,” Dr. House said. “Say, ‘I got an A in this class, but I was disappointed in the way things were graded.’ Those are the kinds of things that will get things changed.”