Bill Gortney stood on the deck of the USS Roosevelt in Mayport, Florida, preparing himself for takeoff. It was spring 1975. He climbed into a carrier plane with “United States Navy” plastered on its side. The engine started; the propellers whirred. Soon the USS Roosevelt was a tiny dot below him.

College student and son of a naval officer, Gortney had decided that a career in the Navy was not his goal. He wanted to be a lawyer. But as he took in the atmosphere of the aircraft carrier – on board and from the air – he saw his future.

“Maybe this is what I want to do,” he thought. After all, he had spent most of his childhood wanting to fly airplanes just like his dad, a retired Navy captain who flew more than 45 combat missions in the Korean War and helped develop a low-level pilot training program for weapons delivery.

Thirty-seven years later, the Elon graduate is a four-star admiral and leader of the U.S. Northern Command (NORTHCOM) and the North American Aerospace Defense Command (NORAD). It’s the first and only position with one military commander in charge of protecting the nation from any potential attacks on U.S. soil.

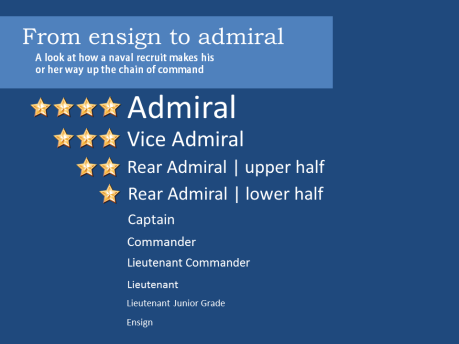

Climbing the ranks

When Gortney returned to Elon College after his experience on the carrier, he was determined to get into flight school.“He saw that direction,” said Les Hall, friend and classmate, “and he made sure he had everything in line to get into flight school.”

Gortney met with a recruiter in Raleigh and planned to take the test to get into Aviation Officer Candidate School (AOCS).

The first time he sat for the test, he failed. It focused heavily on science, technology, engineering and math – not quite the areas of expertise for a political science and history major.

He spent the next six months studying. The second time Gortney sat for the test, he failed.

Graduation crept closer with each test. Gortney continued to study but also signed up to take the U.S. State Department test as a backup plan, just in case.

“I don’t like being told no,” Gortney said simply. “I got the spark again, and it was just something I wanted to do.”

The day before the U.S. State Department test, he received some long-awaited news. After his third try, the Navy had accepted him.

The summer after graduation, Gortney headed to Pensacola, Florida, for basic aviation training. He received his commission in the U.S. Naval Reserves in September 1977. In December 1978, he earned his wings of gold, officially distinguishing him as a naval aviator.

That same year, he started his first assignment as a flight instructor at the Naval Air Station in Beeville, Texas.

Over the next eight years, Gortney completed four fleet assignments, three shore assignments and one command tour, and earned a masters degree in national security studies from the Naval War College in Rhode Island.

He climbed the ranks from commander to four-star admiral, the highest position in the Navy, in a span of eight years. He has served in positions on land at the Pentagon and at sea on U.S. naval ships. He has recorded more than 5,300 incident-free hours in the air, and provided support for operationsEnduring Freedom and Iraqi Freedom in varying roles from 2002 to 2010.

Surpassing goals and receiving accolades did not come without a price. His personal life is always under stress, as is the case for many in the military.

Making it work

Gortney met his wife, Sherry, in high school in Jacksonville, but they knew each other long before they started dating Gortney’s senior year. They hung out in the same social circle with a large group of friends, but never really had one-on-one time with each other.“He loves to tell people that I turned him down,” Sherry said, laughing heartily.

When Gortney left for college in 1973, he and Sherry made it work.

“We’d do this thing called letter writing,” Sherry said. “And we’d talk on the phone Sunday nights at a set time.”

She’d make at least one trip to Elon every year for Homecoming. When Gortney left for basic training, they put the relationship on pause. Nothing changed.

She remained his “secret weapon.” They are their own team. He hardly ever refers to his career without Sherry in the same sentence.

Gortney tried to find the right words. “You find your soulmate. Sometimes, you find it right away; sometimes it takes a little while. Sherry and I have been together throughout this journey, and we’re still madly in love with each other.”

Hall recalled Gortney saying that Sherry would make a wonderful Navy wife. And she has.

“Many of us are fortunate enough to come across a spouse who gets it,” said Admiral William Keating, one of Gortney’s mentors who held the position he has inherited. “They get it done. They have a wide variety of responsibilities like taking care of the kids, family, soccer and church.”

Even with resilient spouses, the Navy life can be a tough, especially on kids. Gortney knew that.

“It hasn’t been without its challenges,” he admitted. “I knew that firsthand being a Navy brat, which is why I didn’t want to be a part of the military. If I was going to get married, I didn’t want to put my family through that challenge.”

Along the way, Gortney learned how to best use the time he had instead of wishing for more. He navigated his way through work life, family life, as well as mental, physical and spiritual health.

“As you go through life, you’re not going to be able to keep those attributes in the right order. Someone else is going to decide for you,” Gortney said. “When it’s time to go on deployment, we put work ahead of family. But when we come back, we put family ahead of work.”

Duty called upon the Gortney family to move four times in five years. They moved up and down the East Coast before settling in Virginia Beach, where their two children graduated from high school.

Work took precedence again in 2008 when Gortney’s first grandson was born. At the time, he was stationed in Bahrain as Commander of the U.S. 5th Fleet.

It was hard for Gortney to be gone for pivotal moments like that, and it will be harder still for him to move to Colorado Springs, where NORTHCOM is headquartered at the Peterson Air Force Base.

It will also be hard to leave the naval families with whom he and Sherry have bonded. They have taken care of these families, given them advice and helped them adjust to life in the Navy.

“When they tell us to move on, we move on,” Gortney said, without a moment’s hesitation. “We’re going to miss working with sailors every day and making our Navy a better place, but we’re going to go out and defend the home.”

New challenges, same attitude

As the leader of NORTHCOM, he will need to communicate and coordinate crises responses with National Guard units and federal units, NGOs like the Red Cross, and the Canadian and Mexican militaries. Since the creation of the command after 9/11, it has mostly responded to natural disasters like Hurricane Katrina in 2005 and wildfires on the West Coast.Gortney would not have been selected if he had not already proven that he could maintain and organize a massive group.

In his role as commander of U.S. Fleet Forces, Gortney managed and oversaw more than 118,000 Navy and Marine Corps personnel on 177 ships. He was in charge of an area that stretched from the North Pole to the South Pole, across most of the Atlantic, into the Gulf of Mexico and Caribbean, and along the Western coasts of Central America.

“He knows what this job entails,” Keating said confidently. “He’s ready. He’s got the right set of attributes they’re looking for.”

Gortney pays attention to detail. He researches a topic thoroughly until he’s an expert. He follows a task through from beginning to end making sure it is properly executed.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?x-yt-cl=84359240&x-yt-ts=1421782837&v=OtHQ4djrsF4

During one of his assignments, he had the opportunity to work with fellow Kappa Sigma and Elon graduate Zene Fearing. One day, he called Lieutenant Colonel Fearing into his office. It was Fearing’s last year in the Marine Corps, but he had not told the admiral he was retiring. Gortney found that out himself.

“Zene, when is the retirement ceremony?” he asked.

“Well, I wasn’t planning on having a retirement ceremony,” Fearing replied. Gortney asked again. Fearing knew what was coming.

Fearing ended up with a retirement ceremony planned by the admiral, “on board the USS Wisconsin, Navy band and all,” he recalled.

Knowing when to take risks

Gortney is too humble to talk about his accomplishments. He cares more about results than credit. If an idea has some merit, he’ll mull it over and decide if it could work. He weighs these ideas seriously, especially when in serious and potentially dangerous situations.“No one knows how it’s going to play out,” Fearing said. “You’re always trying to mitigate the risk. He uses his experience and wisdom to come up with a plan to minimize casualties.”

It’s tough to send someone else into harm’s way. Gortney will not send anyone out if he would not do it himself. Still, pilot errors, mechanical errors and targeted attacks happen. When there is an incident, a commander can only say it was the best decision to make given the circumstances.

It’s tough to send someone else into harm’s way. Gortney will not send anyone out if he would not do it himself. Still, pilot errors, mechanical errors and targeted attacks happen. When there is an incident, a commander can only say it was the best decision to make given the circumstances.

His precision and careful planning led to one of the biggest highlights of his career, putting him in an international spotlight.

Gortney, a vice admiral at the time, led the U.S. 5th Fleet in Bahrain from 2008-2010. During his command, a band of pirates off the coast of Somalia captured a cargo ship in the Gulf of Aden and took its captain hostage. Gortney was given the go-ahead from a higher command to make a decision.

He assessed the situation and determined that the captain’s life could be in danger. He gave the orders for a SEAL team to aid the USS Bainbridge in a possible rescue mission. In the dead of night, they parachuted into the gulf from a naval aircraft and were hoisted aboard. Gortney proceeded to give the commanding officer of the ship the authority to rescue the captain, which he did.

Gortney’s put himself in harm’s way, too. During operations Iraqi Freedom and Enduring Freedom, Gortney flew combat missions. His actions have been rewarded with several Air Medals, which are given to military personnel for extraordinary service in flight during combat.

Paying tribute

Gortney, his wife, their adult children and two grandsons spent one of their last weekends together at the Blue Angels Air Show at the Naval Air Station in Oceana, Virginia this fall.Wind and rain forced the Blue Angels to land midway through the first day of competition. The following afternoon, the sun broke free and the Gortney family turned their gaze skyward.

Gavin and Grayson watched planes dip and dive through the air in awe. “Papa Jet” is convinced in this moment that they like the idea of flying.

This is the second time that the admiral has shared his lifelong commitment with three generations at once. It’s a commitment that for several generations built resilience with each deployment and new school.

Special moments like this, Gortney knew, wouldn’t last forever.

“Being around our family has been a lot of fun the last two years, and we made the most of it,” Gortney said.

He and Sherry are excited and proud to continue serving the nation, even if it’s not what they had in mind for their life together when they wed in 1980. He doesn’t deny it.

“I had no intention of making the Navy a career,” he said. “But Sherry and I just started having fun at the business.”