Every month, a group of women in Alamance County gather at one woman’s house for a book group. They catch up. One asks how the kids are doing, another how graduate school is treating her, and then they sit down to talk about this month’s book.

This scene is not uncommon in the United States. Go to any suburb of any city, and you’ll likely find suburban wives and mothers getting together for book talks and potlucks. What is interesting about this group is how different these women are and how they’ve used these differences to come together in a part of the country that’s long been known for its homogeneity.

These women are of different religions. They are an interfaith book group made up of Episcopalians, secular humanists, Muslims raised as Christians. While this might not seem uncommon, these women live in a state that is more than 46.5 percent Christian. Of those who identify with a religion, 98 percent identify with some denomination of Christianity, according to the 2010 U.S. Religion Census.

These women are of different religions. They are an interfaith book group made up of Episcopalians, secular humanists, Muslims raised as Christians. While this might not seem uncommon, these women live in a state that is more than 46.5 percent Christian. Of those who identify with a religion, 98 percent identify with some denomination of Christianity, according to the 2010 U.S. Religion Census.

The separation of church and state has been an ongoing balancing act in the United States throughout the years, but in the South, or the “Bible Belt,” the separation of church and life has been a more pressing issue. It has surfaced today possibly more than ever before.

A growing number of political debates in the U.S. have turned to matters of religious freedom. Cases like a New Mexico photography company’s decision to refuse service to a same-sex couple for their wedding photos and Hobby Lobby’s objection to the Affordable Care Act’s requirement to provide birth control in its insurance plan are bringing the debate between religious freedom and other rights to light.

“Obviously the separation of church and state is one of these American ideals that’s existed for a very long time,” said Jason Husser, assistant director of the Elon University Poll. “The question is: Is it more important to courts or society as a whole to grant religious freedom or to recognize a right for religious freedom or other democratic rights? Sometimes rights of one group directly conflict with rights of another group.”

Testing the Waters of Alamance County’s Religious Climate

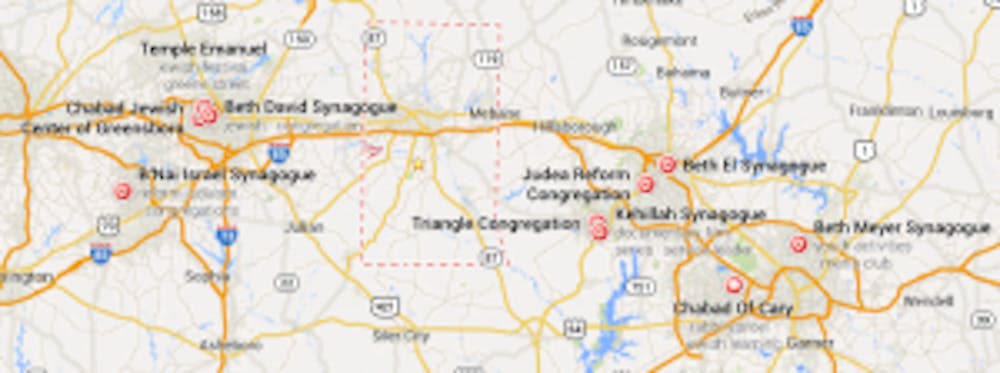

While many metropolitan areas like Raleigh and Greensboro have fairly diverse populations, less populous areas might not include such variety. Alamance County, for example, has a population of just under 154,000, but the county has approximately 290 churches. There is one church for every 531 people in Alamance County, but there are no mosques, no synagogues and no Hindu temples.Shylon Smith, who runs the book group, is a Sunni Muslim who was raised by a Baptist father and a Methodist mother in Alabama. Despite the lack of religious diversity, she feels that the area around Alamance County is more receptive to religious differences than some other places she’s lived up north and in the Deep South.

“I look different,” she says of wearing a hijab in the Muslim tradition, “But in the South, most people are raised in a certain way with manners. There’s just a certain way that they’re raised that even if they think you’re wrong, they just keep their mouth shut.”

Smith says that while some may not be familiar with the traditions of her religion, she has had a much more positive experience in North Carolina, even in this less diverse area.

Some have seen the other side of this predominantly conservative Christian area. Elon University Chaplain Jan Fuller is an Episcopalian minister and writes a weekly religion column in the Burlington Times-News, alongside three male Evangelical ministers.

Fuller says that while her column is typically well-received by the community at the university and at her own Episcopalian church, her column has caused a stir with others in Alamance County.

“I routinely get commentary from the local community about the fact that I don’t quote the Bible enough, that my ideas are not very true…” Fuller says. “[A few weeks ago], I got several comments, one anonymous. One came in the mail from Greensboro with a list of quoted scriptures about how only people who believe in Jesus are going to be saved. So that’s I think a picture of the climate of this area.”

While Fuller has seen a part of the “mean and ugly” side of some locals, she maintains that most residents are not “mean and ugly.” She says she’s only met one or two in her time and has seen many communities make clear steps toward religious diversity and inclusion.

Alamance Native Watches Area Grow

Ginny Vellani has seen this change in diversity first-hand. Vellani, Hillel development and Jewish life associate at Elon, grew up in Mebane as an Episcopalian after living in a Quaker community in Indiana as a young child. She converted to reform Judaism several years ago and returned to Alamance County to work at the university.Vellani has seen the area change from one with few other religious groups than Christians in Alamance County to one that has budding Muslim and Jewish communities. Elon University’s Hillel House is the first Jewish building in Alamance County, and several Muslim communities have been holding prayer meetings in the county, she says. She was even invited to represent the Jewish faith at Alamance County’s Moral Monday protest in October of last year.

“My experience is that people are very interested in learning about other religious communities and faith traditions,” she says. “But I think some of the most interesting interactions are between the Christian denominations because although it might seem simple for Christians to talk to one another, it really is in some ways more complicated to talk to the people who are closest to you than it is to talk to people who are very different from themselves.”

Shereen Elgamal, a professor of Arabic at Elon, is Muslim and also notes that the local community is accepting and interested in learning more. She has been invited to speak at several events at nearby churches and educate people on Islam. Still, she says a fair amount of people are unaware of the religious differences.

“The Muslim prayer involves certain movements… I bow down and prostrate on the ground and whatnot, and people would look at me in amazement,” she says. “I was never disrespected or anything like that, but I could tell that these people had never seen a Muslim pray before.”

As for the younger generation, things are changing. Elgamal says she’s seen this in her students who are venturing out to visit different places of worship for their classes. Vellani has also observed changes in the younger generation – particularly from the way they explore their faith with greater access to resources on the Internet.

“I think [living in a globally connected society] influences people because we’re no longer living in silo’d communities in which everyone we see is the same,” she says.

Millennials, she says, are redefining the boundaries of multiple and intersecting identities.

Interfaith Growth in North Carolina

Rev. David Fraccaro, executive director of FaithAction International House in Greensboro, believes the younger generation is the future of the interfaith movement.“There are a lot of college campuses that are awakening to kind of the more youth-led faith movement so they are kind of a little more aware of being intentional about including people outside of their own faith,” he says. “They’re moving beyond dialogue; I would definitely say they’re interested in action and service.”

Fr. Gerry Waterman, the Catholic Campus Minister at Elon University, has watched Elon’s campus undergo many changes during his nine years as a result of the movement towards engaging students of different faiths.

“What began as a very small multifaith and interfaith operation has become a very large-scale operation, hence… the multifaith center,” he says. “It’s come a long way, and the emphasis on trying to attract students of many, many cultures and diverse backgrounds and faith traditions has been a forthright effort that Elon has put out in the last couple years.”

Waterman believes the residents of the surrounding area are changing their minds as a result:

As the greater community works to accept more people from different faiths, Shylon Smith and her interfaith book group are already paving a path towards greater interfaith acceptance on their own. Amal Khdour, a Sunni Muslim woman in the book group, sees the good in what their group is doing.

“When I look at our book club from different religions, different ethnicities, different backgrounds, different beliefs,” Khdour says, “I think the whole purpose in our life, we’ve been created different like that so we can meet each other, know about each other, learn from each other and live together. That, I think, is the whole purpose of our entire lives.