Everyone who has endured a winter at Elon University knows that nothing is predictable, except for one thing: as temperatures drop, numbers on thermostats rise.

To face the demand for higher temperatures on the thermostat, Physical Plant works around the clock to ensure that residential buildings and academic spaces are suitably heated while aiming for a temperature range that falls to around 68 degrees — one they deem both appropriate and environmentally-aware.

But the imposed limit has become a cause of discomfort for some students at Elon who find that their residential spaces are too cold.

Maria Hadaya, a sophomore who lives in Colonnades, said that though her room would heat up to around 70 degrees, she had to seek alternative measures to stay warm.

“It was just too cold and it took to long to heat up in the first place,” she said. “I had to buy a space heater because I was so cold. It was the only way I could stay warm.”

According to Robert Buchholz, director of Physical Plant and the figure who drafted the 68-degrees policy, the number reflects extensive research but has nothing to do with Physical Plant’s budget.

“It’s a number that, as far as talking about energy conservation, has been around for a long time,” he said. “Part of my research involved checking with other universities, and I found that the norm was 68 degrees.”

The Association for the Advancement of Sustainability in Higher Education (AASHE), a program that Physical Plant partners with, also listed in a 2011 report that its recommended temperature range is from 68 to 72 degrees. During the energy crisis of the 1970s, city, state and federal administrators, including the Navy, also imposed a 68-degree limit.

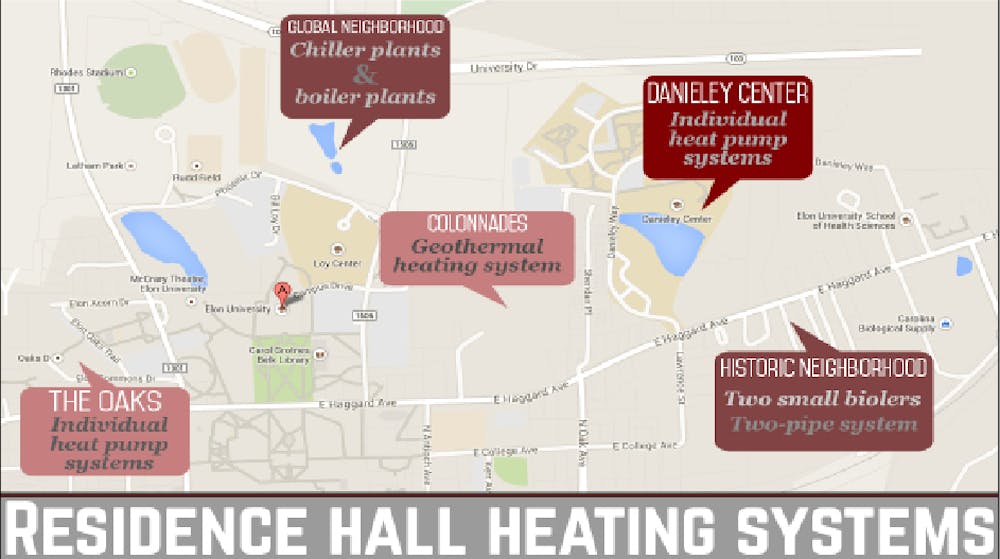

According to the Office of Sustainability website, Elon’s policy on heating and cooling is based on degree-days, a formula that relates each day’s temperature to the demand for fuel to heat buildings. The average of the high and low temperatures of the day are calculated. If the result is greater than 65 degrees, then those would be cooling degree-days. Conversely, if the average is below 65 degrees then the difference would be heating degree-days. But Buchholz emphasized that while Physical Plant does their best to ensure that the temperatures fall in the requested range, there isn’t much they can control as the university relies on several different kinds of heating systems including steam ventilation and geothermal heating. Though they regularly monitor temperatures, the desired range can be surpassed in many residential spaces.

“Every room is independent,” he said. “We do our best to maintain the range, but sometimes it doesn’t always work, and I don’t always have the ability to control it in the first place.”

Buchholz, with more than 38 years of experience in facilities including similar heating policies, said finding a universally satisfying temperature range for large groups of people with varying degrees of comfort is almost impossible.

“I used to get calls from two people in the same office with one complaining that it was too hot and the other saying it was too cold,” he said. “Even now at Elon we still have students that leave their window open, which is highly damaging to buildings given the low temperatures and others that are too cold.”

Still, he encouraged students to visit the office with any proposals to change the policy.

“Elon has always been an open, friendly place and I wouldn’t have any problem with students coming to talk about it,” he said.

Elon’s environmental efforts have not gone unnoticed. Elon was a recipient of federal grant money through the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act that helped with the installation of solar thermal panels for heating water in Colonnades Dining Hall and four residential buildings. Eighty-two solar thermal panels were installed and are expected to prevent 49 tons of carbon emissions each year.