Nearly one-third of children in Guilford County who were eligible for childcare subsidies in 2013 did not receive it. Instead, they were left waiting. In 2015, they are still waiting.

These children are waiting for help, affordable childcare and a place to thrive while their parents work. They are waiting for the long-overdue house repair and basic healthcare. Low-income families may have to sacrifice basic necessities for the sake of their childcare.

Dozens of families turn to the Department of Social Services and the Guilford Child Development Center for assistance. Once on a wait list, they receive a federal childcare subsidy. But when the centers refer them to an adequate childcare center — those families who waited for a referral end up on another wait list.

Tanya Robinson-Caldwell, parent services coordinator at the Guilford Child Development Center, said, “some programs still have a wait list.”

Robinson-Caldwell refers families to childcare options that match their needs. She said many pre-K programs do not offer financial aid and families can be offered childcare at hours that don’t match parents’ work schedules.

Between the difficulties of finding care, getting off the wait list, affording childcare and ensuring the center matches one’s work schedule, Robinson-Caldwell said finding childcare is no easy feat.

Employment doesn’t ensure financial stability

In 2014, the North Carolina General Assembly implemented budget cuts and changes to the childcare subsidy system. Its purpose was to close down sub-par centers to ensure a higher quality of care. WFMY News reported the assembly’s goal was to serve the neediest families, focusing the states limited dollars for people most in need. It has now been a year since the cuts and many families are still suffering.

“The budget cuts were a gift and a curse,” said Fanta Dorley, a representative for the Family Success Center who is involved with processes and policies of the integrative services for United Way of Greensboro. “It puts a strain on the waiting list now — there are lower slots available for families to have the option to take.”

Dorley said if there was no time limit on how long a family could use the subsidy, there would still be a waiting list. And if the families used subsidies solely for managing childcare costs, the waiting list would continue to grow.

Sherri Henderson, executive director at the Boys and Girls Club, said the club's enrollment increased tremendously after the budget cuts.

“The club did benefit by enrolling new members, and the parents were very happy to have their school age children attend a structured after-school program than having their child at daycare,” Henderson said.

The club’s prices of $25 a week for one child, $45 for two children and $65 for three children are 50 to 100 percent less than most other programs. Families that were put on outside waiting lists or who were dependent on assistance flocked to The Boys and Girls Club. When the cuts were implemented, there was a rise in families on waiting lists due to the closing of under-par centers and decrease of subsidy availability. Some families, who may no longer qualify for help or who would be stuck on a wait list, came to The Boys and Girls club instead — hoping to have affordable, quality care.

Henderson said the club now has a waiting for the first time.

The waiting list has allowed families to be more resourceful — such is the case of Elizabeth Robertson, who opted for a dual job-childcare scenario.

Robertson is a single mother of four living in Guilford County. She receives SSI (disability) and Section 8 Housing as forms of welfare. She is taking a GED course at the Guilford Child Development Center.

Robertson's income is dependent on her 16-hour work week at Wendy’s, where she, her friends and her co-workers speculate on a life free from fiscal barriers. Robertson pursues an education that works well for herself and her children.

She hopes to help other families that have faced similar scheduling challenges from waiting lists by creating a daycare center.

“I just want to run my own daycare now,” Robertson said. “I think that’s what I can start with, something I can actually start doing now instead of waiting.”

By running her own daycare center, she would not only be providing her children with free and easy-access care — she would have more financial stability.

“I plan to start the certification class in January,” Robertson said. “Hopefully, I will be able to start the daycare center next year.”

Childcare is a necessary sacrifice

While childcare provides parents the ability to work, it also provides children with socialization — an essential cognitive development that can ensure a higher success rate in school, according to Bernard Curry, an assistant professor of sociology at Elon University.

“They need to interact in terms of nonverbal and verbal communication,” Curry said. “They need to learn how to comply, how to conform, so if an adult says ‘everybody get in a straight line,’ they know what the adult is talking about.

Video Clip: Elon Professor Bernard Curry talks about the importance of childcare centers.

It might be cheaper to rotate kids with family babysitters in the neighborhood, but socialization could be deprived in the process.

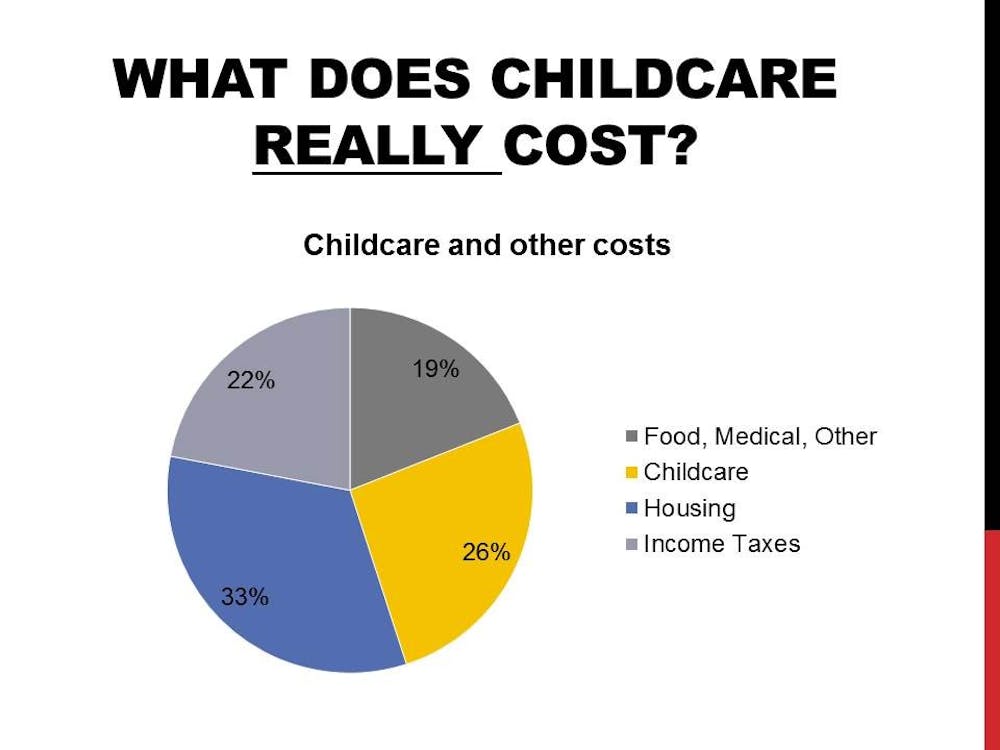

Though many low-income families want the best possible care for their kids, they face dilemmas and spend a significant portion of their working wages on childcare.

"Childcare is very expensive, but on the other hand, I'm still better off working and paying childcare," said Donna Chandler, financial planning specialist at Elon University.

Chandler works full-time, and while her job does ensure her a stable, healthy life, it’s not one sans-sacrifice — childcare prices affect her, too. She pays over $8,000 a year to ensure her daughters are cared for after-school. She said she brings home enough to provide and have more than enough left over to pay for other expenses, but that no one’s socioeconomic class is a stranger to large checks going towards childcare.

“Affordable childcare is applicable to all, no matter what ‘class’ because that is a huge portion of your monthly paycheck,” Chandler said. “If you didn’t have to pay such large amounts of childcare, you’d have the money to do other things, pay for other things that you can’t now.”

Why are childcare workers some of the lowest-paid employees in America?

Henderson has been working at The Boys and Girls Club of Alamance County for 27 years as the executive director. The club is a non-profit, and Henderson knows their mission is to serve the kids, not themselves. Not only does she experience families not being able to pay their bills, she recognizes staff members are not paid high wages, either.

“Unfortunately, our staff is not paid a high salary,” Henderson said. “It takes an extremely compassionate person that is very dedicated to working with those less fortunate to do the work that we do.”

Daniel Marans of The Huffington Post reported that childcare workers are often not paid enough to make their own ends meet. According to a report published on October 29 by the Economic Policy Institute, the national media pay for childcare workers is $10.31 an hour. The poverty rate among childcare workers is 14.7 percent, which is nearly twice the rate for other American workers, which is 6.7 percent.

Yet childcare is prohibitively expensive for most American families, Marans reported.

Is there an answer?

Curry said upping the minimum wage may solve affordability issues.

“In America there should not be this — families shouldn’t be struggling to the extent to where they need to make the choice between feeding their child or providing medication in order to pay their childcare bill,” he said.

“It’s a catch 22,” Robinson-Caldwell said. “Families can’t afford childcare, but need a certain amount of hours in order to qualify for assistance.”

It’s also a waiting game — looking to find the perfect puzzle piece to fit financial, emotional and physical needs.