Click below to listen to the radio version of this story.

Thousands of miles from Elon, a nation is in crisis. Millions of Venezuelans have left their country in a mass exodus, fleeing a plummeting quality of life. While thousands hike across land borders every day, seeking refuge from food and medicine shortages and street violence, others have departed for the United States, and some of them have ended up here at Elon University.

Senior Emiliana Lanz is one of them. She remembers seeing the suffering up close during a recent trip back home.

“You go outside, and everywhere there’s people eating out of the trash and in very bad situations,” Lanz said. “Just suffering because they don’t have medicine.”

Government corruption and mismanagement have spurred economic catastrophe. Hyperinflation of the bolívar, Venezuela’s currency, has made it near impossible to buy even the most basic of items. A pack of toilet paper costs the equivalent of a month’s salary. Some have turned to crime out of desperation, making robbery and kidnapping commonplace.

“It doesn’t matter what time of day,” Lanz said. “Doesn’t matter where you are, there’s always a risk. You can’t be in your car on your phone because if someone sees you on your phone, they’re going to try to steal it from you, and they’re going to point a gun.”

It’s hard to find food, unsafe to go out on the streets and harder still to pursue a degree. Venezuelan students at Elon University say they came here for a level of education that’s absent in their home country, but most of them are leaving family behind.

Lanz is in constant contact with her parents, who are still down in Caracas — the nation’s capital — with her brother and other relatives. They send her updates about outrageous prices and the latest anti-government protests. She says it can be tough to keep her mind on schoolwork with her whole family facing such dire realities, but she’s staying hopeful.

Home country in the headlines

International headlines have lately been dominated by tales of suffering and escape in Venezuela, which sits on South America’s Caribbean coast. News outlets in the United States have been awash with bulletins describing the latest political goings-on and the daily hardships faced by those in their wake.

In the past few weeks, those headlines have mainly been concerned with assaults on the stability of the sitting government. President Nicolás Maduro’s regime is teetering on the edge of collapse, as opposition leader Juan Guaidó proclaimed himself the country’s legitimate president and garnered widespread support from Venezuelans and foreign governments alike.

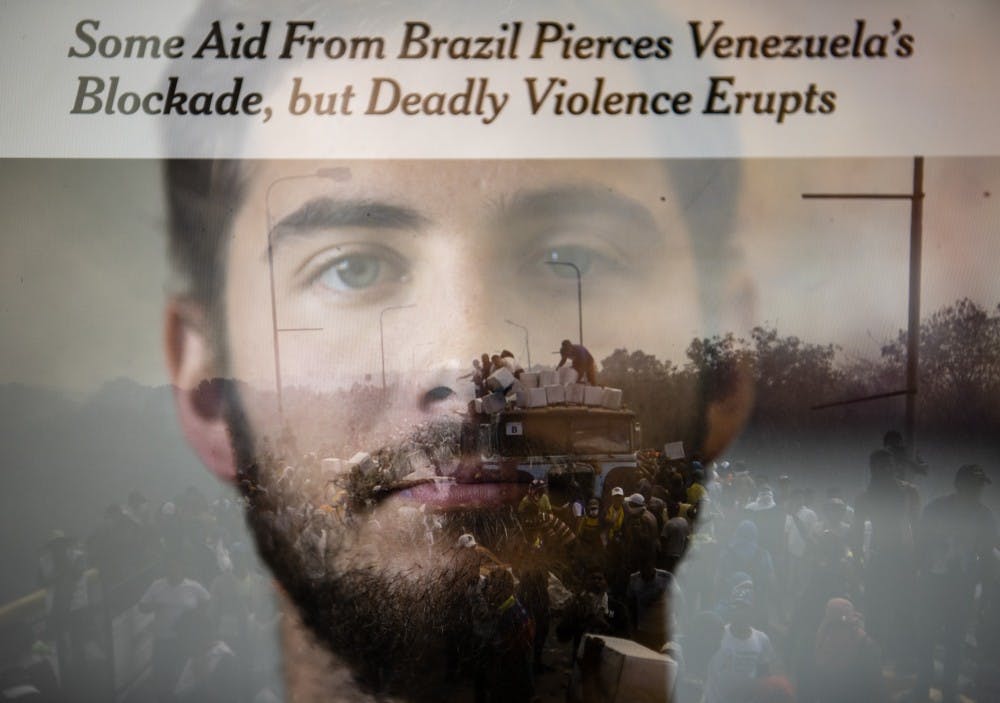

Maduro, who assumed power after the death of Hugo Chávez in 2013, is largely blamed for Venezuela’s economic tailspin. Just this week, he turned the eyes of the world to Venezuela by denying entrance to truckloads of foreign humanitarian aid — supplies desperately needed by those inside the border.

While the stories have ranged from analyses of the political situation to profiles of the hungry and desperate, they’ve been underscored by themes of poverty and misery. For Venezuelans abroad, they don’t paint a pretty picture of the place they call home.

“Everything that’s on the news is just, it’s just dark,” said junior Ricardo Blohm. “It’s all negative news. There’s nothing good about it. No one talks about Venezuela as a rich oil country, how we have one of the seven natural wonders of the world — no one says that anymore.”

Blohm, who came to the United States to start high school, says it’s sad to see the place he’s from painted in such a negative light. Others agree that it’s uncomfortable but say that those kinds of narratives are a necessary step on the path to making things better.

“I like that it’s been portrayed that way actually,” said sophomore Diana Marin. “I know that there’s some people that are like, ‘Oh no, but that’s not the Venezuela we are. People are going to have this bad impression.’ Well that’s reality. That’s what’s happening. The point is to show people what’s happening raw. You cannot sugarcoat it.”

That reality has been felt viscerally by Marin, who says clashes between protesters and police became so normal that she just got used to the smell of tear gas wafting through the streets.

Marin and other Venezuelan expats have been forced to come to terms with the fact that their memories of a more peaceful time are just that — memories. Their childhoods, free from tear gas and food shortages, are far different from the lives of Venezuelan children today.

“People are just very stuck in their homes,” Lanz said. “I think kids right now are probably growing up in a horrible situation, sadly, because they’re not getting what they should get. Like the experiences they should get as a kid, playing outside and doing all these fun things.”

Marin has been able to see that difference firsthand. Her brother and sister, both younger, are still in Caracas. Try as they might to go to school and live normal childhoods, Venezuela’s humanitarian crisis has gotten in the way.

“Just thinking about my siblings having to go through all of that every single day growing up there,” Marin said. “It’s hard.”

The return

When holiday breaks roll around, most Elon students head back home. Planes, trains and automobiles haul them en masse to homes across the country and across the world. But for some of the Venezuelan students, that’s not an option.