Elon university senior Amanda McMahon’s school day begins at 6 a.m. when she wakes up, drinks her coffee and carpools to class. She arrives by 7:30 and uses the spare time to organize her materials for the day. But when the students file in for first period, she doesn’t join them at their desks. McMahon is teaching the class, not taking it.

Nearly 50 education majors are spending their senior year spring semester as student teachers in local, public or charter schools, according to Ann Bullock, dean of the School of Education and professor of education. Once placed in classrooms that correspond to their majors, the student teachers move through a program where they become full-time teachers of the classroom, and the previous full-time teachers become their observers.

Bullock said this program is meant to prepare student teachers for success in a variety of settings.

“We provide opportunities to teach at schools that are very diverse racially,” Bullock said. “We provide opportunities to teach in schools that have low-income children that are in homes with more need. We provide them the opportunity to be in schools that might look more like the schools they went to or not.”

Senior Courtney Kobos, an English major with a concentration in teaching licensure, said she felt ready to take the next step toward her career.

“We’ve observed in so many classes that now we’re excited to have students of our own to get to trust and have some control of the class,” Kobos said. “It’s very exciting to be at that stage where you do have that control and you get to see things come into action.”

But for some of these seniors, the transition from being a full-time student to teaching students themselves has been a learning curve.

Senior Colleen Cody, a special and elementary education major, said nothing had fully prepared her to teach a multiple exceptionalities class.

Cody’s kindergarten through second grade classroom hosts five children with varying disabilities, such as Down syndrome, cerebral palsy and short-term memory loss. Although the class sticks to a schedule, Cody differentiates her lessons based on each student’s individual needs.

“For the students that are nonverbal, there needs to be an adaptive communication point,” Cody said. “If I’m asking him a question, ‘Can you show me a three?’ instead of counting to three, he would point to three, click that and then it repeats back to him, ‘three.’”

For Cody, it’s the little triumphs that are the most rewarding, such as when she heard one of her nonverbal students speak for the first time.

“He’s in kindergarten — he’s five — and he has Down Syndrome,” Cody said. “We get him to sit still at the whole group section of the classroom. We’re doing writing, and I’m trying to teach him how to write his name, so we move a letter to a spot. Instead of him saying what letter it is, he’s pointing to it. And he just started screaming in this voice that we’ve never really heard before. ‘I want to get down! I want to get down!’ And even though it had nothing to do with anything, he was able to express that he was frustrated. We heard his little voice, and it was the cutest thing ever.”

Cody said Elon’s special education majors are taught how to accommodate mild to moderate learning disabilities, not moderate to severe.

“What I’m dealing with is feeding students and teaching them daily essential tools,” Cody said. “I’m telling them how to get up and really live their lives. It’s not a lot of literacy and pushing math. Even though we are teaching that stuff, it’s not the top priority.”

But the real test is yet to come for these student teachers — literally.

Kobos has spent months preparing for Pearson’s Educator Licensure and Performance Assessment (edTPA). She and her peers are tasked with compiling a three-part portfolio to submit for their accreditation.

The portfolio’s first section is lesson planning, which includes detailed accounts of the material and the meaning behind several days’ worth of classes. For the next section, student teachers film themselves delivering their lessons to a class. Finally, the assessment of the portfolio logs the student teachers’ testing methods, including any accommodations they provide.

Kobos said the edTPA is similar to the SAT or ACT.

“I am more prepared than the people who graduated last year, but they really only started talking about it my junior year,” Kobos said. “Any free time I have, I’m working on that.”

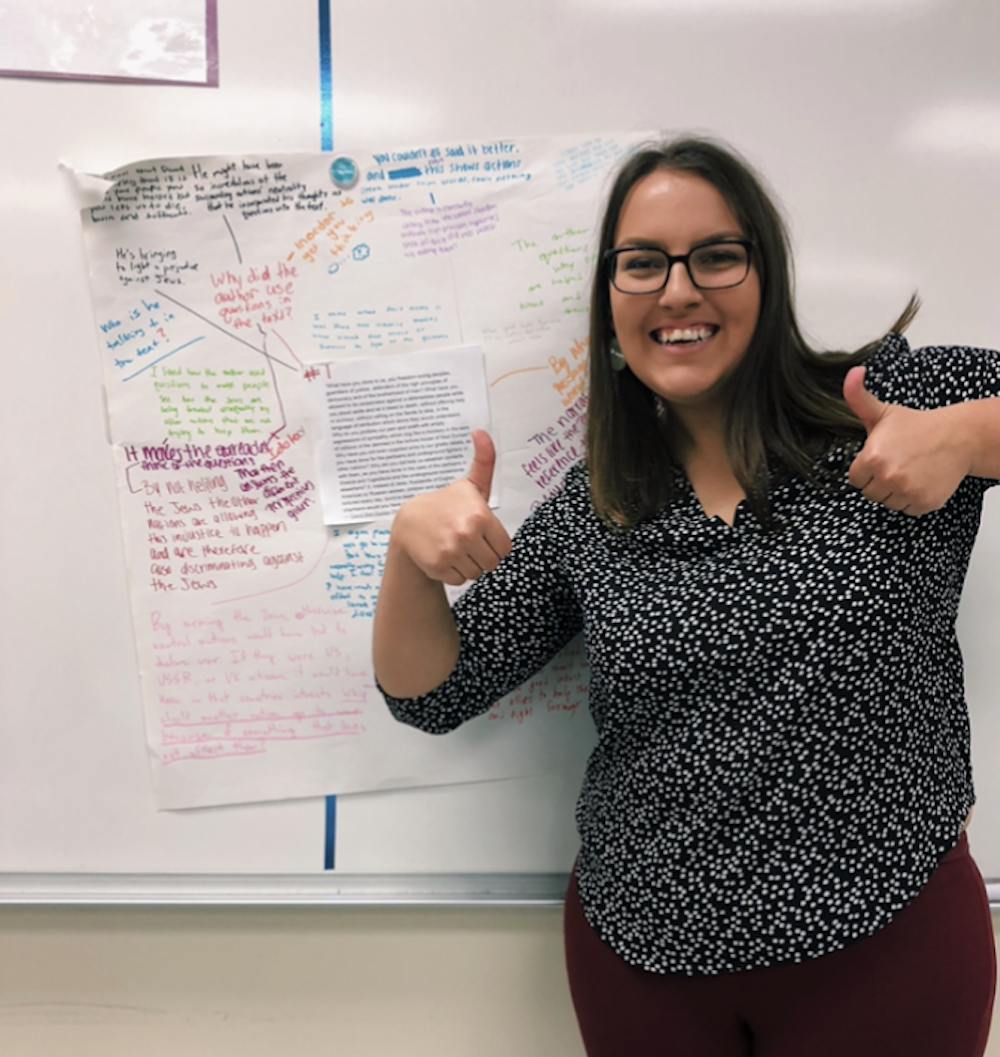

McMahon, who is also an English major with concentration in teaching licensure, dedicates a similar amount of time to her edTPA portfolio. She said she feels her free time is in short supply these days.

Although she enjoys the energy and humor her high school students bring to the table, McMahon said that kickstarting her career has pushed her to grow up.

“When I was still taking college classes, I napped a lot, and it was really easy to put off responsibilities,” McMahon said. “But with student teaching, it’s just not possible. Things are going to keep moving whether you’re there or not, so you really have to be on it. I can’t take a nap in the middle of the day. I have to get up and go to bed early, or things will fall apart.”

For most seniors, their last semester of college is a time of relaxation and celebration. Kobos has struggled to strike a balance between her work and her social life.

“Your students really do come first,” Kobos said. “It is your job to make sure that they have the best education that they can possibly receive. So even though you’re really busy as a student, it’s making sure that you’re really going to bed at a regular time, and your meals and lunches are prepped and ready, and you really do get enough rest over the weekend so that you’re ready to go on Monday morning.”

Cody echoed Kobos’ concerns and said if she had known how much work was ahead of her, she would have spent more time with her friends. She has gained a newfound appreciation for her own teachers.

For however jarring their adjustments have been, these seniors’ experiences have not deterred their passion for education.

After graduation, Kobos hopes to teach English language learners abroad through a Fulbright Scholarship.

Cody has found her niche teaching students with varying learning disabilities, and she may remain in North Carolina for a year before heading back to the Long Island area. Next week, she will be transferred out of her multiple exceptionalities class and into a standard fourth grade class.

“I’m going to lose my mind because my kids are like my kids,” Cody said. “It’s going to be so different going from a classroom of five students to a classroom of 22 students, and they’re in fourth grade. Why couldn’t I get kindergarten or something?”