Lucia Jervis, a senior at Elon University from Ecuador, said she never thought of herself as White until she came to Elon. But when she was filling out basic paper to apply to college in the United States, she had to place herself into a category.

“I remember asking my mom, I don’t know what to fill in,” she said. “And my mom was like, ‘Well, white. All our family’s from Europe.’”

On many federal and state forms, Hispanic or Latino is not an option to the question — What is your race?

The U.S. Census Bureau uses two categories to identify a person — race and ethnicity. Race is focused on outward appearance and ethnicity is focused on country of origin. The Bureau tracks a person with origins from Spanish-speaking countries as “Hispanic,” and people with other origins as “Non-Hispanic.”

Race is a different category. “White,” “Black,” “Asian” and “Other” are common race labels. To those who identify as Latino, like Jervis, the question of race that the U.S. Census Bureau poses can be difficult.

Jervis said that her mom told her to check off “Hispanic” on forms when applying to college, since she is from a Spanish-speaking country. But she reported her race as White.

Researchers argue the difference between race and ethnicity on forms becomes a major problem when states are tracking arrests. The Urban Institute, a social and economic policy research organization, has been analyzing the impact of the difference in race and ethnicity in state and county criminal justice systems. In a study published in 2014, it found that 15 states do not report ethnicity on arrest forms.

The report said, “A state’s failure to collect and report ethnicity data affects not only Latinos but the entire criminal justice system. States that only count people as ‘black’ or ‘white’ likely label most of their Latino prison population ‘white,’ artificially inflating the number of ‘white’ people in prison and masking the white/black disparity in the criminal justice system.”

North Carolina is among the 15 states that Urban Institute found did not collect and report the ethnicity of an individual arrested.

Eddie Caldwell, executive vice president and general counsel of the North Carolina Sheriff’s Association, said that the reason North Carolina sheriffs departments don’t track ethnicity data is because they aren’t required to. When someone is arrested, the first piece of documentation they will show is their license, Caldwell said.

Ethnicity is not used to identify an individual by the North Carolina Department of Motor Vehicles, but race is. Caldwell said race is easier to report than ethnicity.

“Ethnicity is something that is very difficult to determine," Caldwell said. "People are easily, and often wrongly, criticized for making assumptions based on how they think somebody looks."

Vanessa Bravo, associate professor of communications at Elon, with specializations in government-diaspora relations and migrations, said leaving out ethnicity on arrest forms leaves the door wide open to the possibility racial profiling.

“If they really are counted as white, then they become invisible, for example, to understand,” Bravo said about Latino Americans.

Bravo said if a police department is arresting Latinos at a higher rate, it would be impossible for researchers to tell. When Latinos are reported as white she said they are hidden.

Brian Long, assistant Burlington Police Chief, said his department is “very much interested” in analyzing his office’s arrest data to make sure they are not racially profiling. He said his office is constantly checking its numbers to ensure they are not arresting those marked Black more than White.

When filling out an arrest form, Long said officers are trained to ask individuals to identify their race or use the race listed on someone’s license.

“On the front side, we train people to investigate not based on race, but positively on the individual,” Long said. This is to avoid racial profiling, he said.

But, it is impossible for them to see if they are arresting Latinos at a higher rate since their office does not track ethnicity.

“We can’t break down Latino,” Long said. “We struggle with that.”

He said his office would “not object” to tracking ethnicity on its forms. Burlington Chief of Police Jeffrey Smythe has been vocal about bettering its relationship with the Latino community in the area. Reporting ethnicity would be a step in that direction.

Many forms the Burlington Police Department (BPD) uses come from the State Bureau of Investigations, Smythe said.

“The state has never been real clear on those," Smythe said about race and ethnicity on the SBI forms.

He said when he began at the police department in 2013, the office only had two Spanish-speaking officers. Now his department has six. He said he worked hard to build trust through community programs and police academies held in Spanish.

Felicia Arriaga, assistant professor in sociology at Appalachian State University, studies racial profiling in relation to traffic tickets. In North Carolina, it has been state policy to gather and report ethnicity, race and sex of each person stopped, searched and given a citation at a traffic stop since 1999, according to Senate Bill 76.

Arriaga's research focuses on examining racial profiling at traffic stops because there the data is more available to her. But she said that gathering data on ethnicity is about more than getting an accurate representation of a population.

“Is it just a challenge to the point of like, data accuracy? Or like, is actually a challenge because there are systematic and disproportionate types of things happening,” Arriaga said.

How race and ethnicity affect Alamance County

Alamance County's Hispanic population is 4 percent higher than the state average, according to the U.S. Census Bureau.

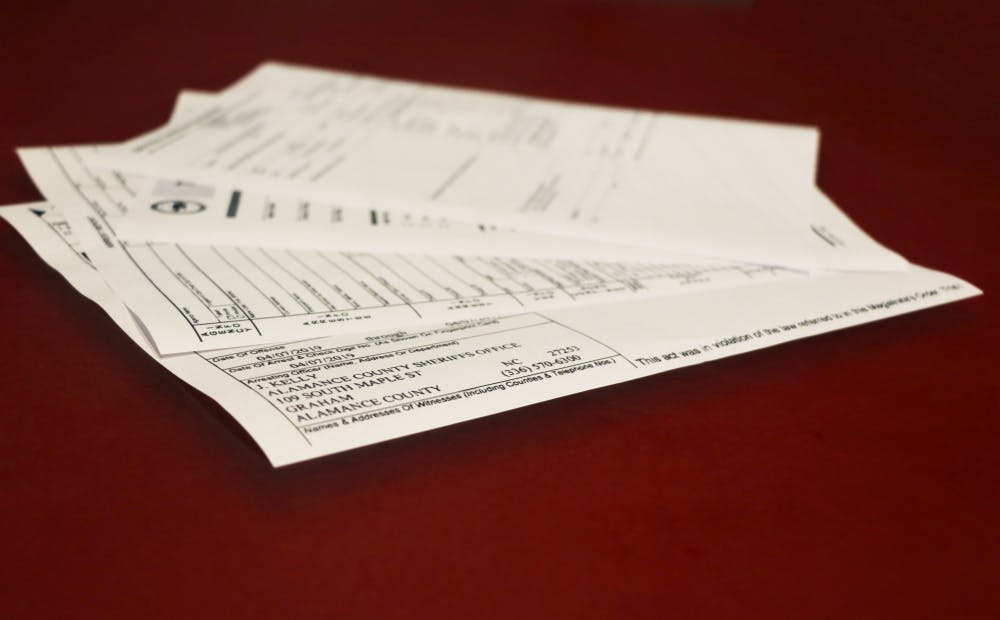

The Alamance County Sheriff's Office (ACSO) and the Burlington Police Department do not record someone’s ethnicity when arresting them. They each only report and collect race.

Mark Dockery, sergeant for the ACSO, said that it is not necessary for their office to record ethnicity, so it doesn’t.

“Basically, we do not collect ethnicity data because it has historically not been a part of standardized state forms,” Dockery said in an email. “There is a way to track it with modern software — although the forms still do not call for it — but we simply do not collect that data just as we do not collect other data that is unnecessary for our purposes.”

Terry Johnson, Sheriff of Alamance County, is a vocal member of the community. He often refers to the Hispanic population in public meetings and in media interviews.

Most famously, he said at an Alamance County Board of Commissioners meeting in January that “illegal criminal aliens is raping our citizens in many, many ways.” Johnson was referring specifically to Latino immigrants. His claim was a part of presentation to show that immigrants were committing the crimes in the count and a danger to the community.

But the ACSO does not track ethnicity. It only tracks race, like all sheriffs departments in North Carolina. There are no numbers to support or contradict his claim. Local researchers claim it is almost impossible to tell what ethnic group commits the most sex crimes in North Carolina counties.

Frank Baumgartner is researcher and professor for the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and expert in racial profiling. He claims that the ACSO is “on shaky ground,” with claims that the Hispanic population commits a high number of sex crimes in Alamance County.

Baumgartner, whose research looks at the North Carolina Division of Courts’ records found that in the last five years less than 2 percent of people arrested for sex crimes in Alamance County were labeled Hispanic. Over 60 percent of people arrested for a sex crime were labeled white in court records.

This data is available because when a Latino is arrested and processed, they are labeled by the courts as Hispanic. But rather than Hispanic being listed as an ethnic category — as the U.S. Census Bureau identifies Hispanic — it is a race on its own in the Division of Courts. This identification is unique.

The ACSO reports ethnicity in its traffic reports because of the state's policy. In 2014, the office was sued by the Department of Justice for racially profiling Latino Americans during traffic stops. The DOJ dropped the lawsuit, but according to calculations from Elon News Network in 2016, from January 2009 to 2012 the ACSO was twice as likely to stop a Hispanic as a non-Hispanic.

The community responds

The non-profit organization Faith Action International House in Greensboro is working to develop a solution and represent Latino Americans, and all international people, across the state. Faith Action asks local police, hospitals, banks and more other entities to accept its community ID.

Some international residents may struggle getting basic identification like a license because of the paperwork required from the North Carolina Department of Motor Vehicles, according to the Director of Education and Advocacy for Faith Action Sofia Mosquera. While the community ID does not replace a state ID like a license, it helps these organizations identify international people.

The cards initially had "country of origin" listed on them, but has discontinued to avoid racial profiling, Mosquera said. The program does not advertise itself as a solution to a systemic problem of how Latinos are recorded in the criminal justice system, but Mosquera said it is headed in the right direction.

Mosquera said that the point of the program is to build trust between local law enforcement and the international and immigrant community.

“We try to have that bridge-building work,” Mosquera said. “Because otherwise we realize these communities will not talk to each other.”

Smythe said he understands the value of using this ID. He decided to make it a corporate policy to take the Faith Action ID into consideration when citing or arresting a person. The BPD hosts ID drives and forums in addition to this policy.

“The first and most valuable part of the program is that it builds trust with the local police department,” Smythe said.

Local pharmacies and hospitals have also agreed to accept the community ID. But, the ACSO does not have the same policy. Instead, it is up to the discretion of each officer in the field. But, if someone is Latino and arrested with a Faith Action card, they could still be labeled as white on arrest forms.

The North Carolina house also recently proposed a bill to conduct a statewide study to examine criminal justice data and how it is collected. It is still under review. Neither race and ethnicity are directly stated in the bill.

House Bill 885, if passed, would study data being collected by each local and regional detention facility. The study would look at information collected on admission to the facility, population, revenue and costs and the process each jail collected, recorded, maintained and searched this information.

Arriaga is interested in the direction of the bill. She said she hopes that officials, along with the NCSA, will take a closer look at traffic stops and arrest forms to reduce the chance of racial profiling.

“There should be a broader conversation between the Sheriff's Association and Police Chiefs Association to have a conversation around people who are tracking some of these things,” she said.