Joseph LeMire began his new role as Elon University’s new chief of campus safety and police on March 29. LeMire entered the field 28 years ago after he was inspired in high school by his uncle, who worked for the Chicago Police Department. LeMire comes to Elon from the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, where he served as the chief of police and the incident commander for COVID-19 response.

LeMire began his career in the Hannahville Indian Community in Wilson, Michigan. He then spent 13 years in the department of public safety in Escanaba, Michigan, where he served in multiple roles. Before going to the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, LeMire was a lieutenant at and then chief of the University of Wisconsin-Oshkosh police department.

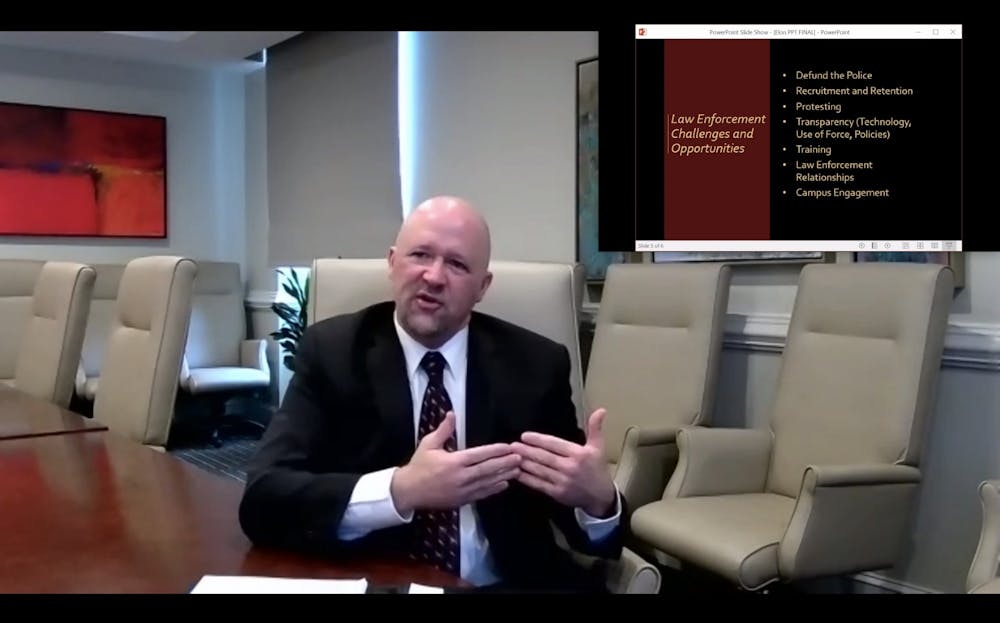

Elon News Network spoke with LeMire about his plans for his first days on campus, his thoughts on the mutual aid agreement and how he will connect with the Elon community.

This interview has been edited for clarity.

What do you hope your first few days look like here on campus?

It’s really going to be a little bit about listening and taking tours to learn as much as I can about Elon, so I can apply my input and my experiences to: how do we make campus successful; how do we make the police department successful; and how do we get us to that collaboration point that I’d like to be at? So, a lot of meetings to start off, but I think that’s important to make sure that … I can’t come in with preconceived notions that I’m going to change any one thing, because what worked at UW Milwaukee may not work at Elon. I think it’s important for me to keep an open mind and listen to the people that are already in that position because Elon is a successful place. It’s a great university.

What are your thoughts about the surrounding community and how the surrounding areas will impact your job here?

In Milwaukee … we created a plan where we worked with the local police department to: one, make sure its students were safe; two, address quality of life issues — parties or things of that nature; and then, through the university, there was an educational piece that if students needed help with their landlord, students needed help with local police department, you know, things that they need. So, we had this three-legged stool … We didn’t over-police the students or anything like that; we just treated it more as an educational component. At times, there was enforcement, but it was those cases where there were multiple contacts with somebody and things like that. So that compassionate approach, but also involving our dean of students and things like that really was successful. We want to make sure that we’re always a resource and [we] provide help, provide education, work with local authorities — whether it’s a town of Elon, Burlington, Graham — where a student might be involved.

From a Title IX perspective on a campus, if the student was sexually assaulted, sexually harassed, things of that nature, [we want] to make sure we have those contacts, so resources could get to the student … The police department is one of the best contacts with those local authorities to hear about if they had contact with a student. And how do we make sure when they come back to campus that — whether it’s counseling, whether it’s health, whether it’s something within the residence hall system, maybe the person involved in the sexual assault is also a student — how do you make sure the person is safe? How do you make sure they have the resources they have? So my contacts with local authorities, I think, are very important. As [are] the other people are my staff, and I really advocate that we keep those levels of communication open and work with them for the benefit of the students.

What are your thoughts on Elon’s role in the mutual aid agreement, and what do you see as your department’s role in that?

I think where some of the discussion came up for Elon was it was a pre-planned event … In a pre-planned event, I think what’s important to say — in that case I think they’re talking about a protest event — the police department’s not taking a stand on any particular position of a protest. It’s more the safety of the area and those local residents.

So if the police department from Elon came over to help another city, we should be going over maybe to help other services, maybe a block road, maybe help with something else while the local police department deals with the event itself, as opposed to the police department going in to deal with their event. And I think that’s an important, distinguished piece to that.

Now, ... I haven’t been there, so I don’t know exactly what was behind the whole story, but it’s something I would have a discussion with people just to find out the parameters of that [memorandum of understanding] agreement. Because what I’m finding a little bit is ... the pendulum has swung, and people are talking about, maybe severing ties with other law enforcement agencies for MOUs, and contacts and sharing of information. And if people remember back to Virginia Tech when they had the shooting at the university, one of the after-action reports talked about how there wasn’t sharing of information, even on campus. There was silos of information and nobody shared, and had that been shared [and the departments] worked together, the event and the shooting could have been prevented. So, I’m very cautious of that piece: that other police departments, and even Elon, need the help of other agencies.

When helping a student who may be experiencing either a sexual assault situation and or a situation like a mental health crisis, the police department may be notified and asked to help. What do you see as the university police department’s role in situations like that?

There’s a lot of discussion on whether police would handle mental health type calls. And I think there’s still a spot for that because the police are a 24/7 operation. I would say probably 80% of my staff in Milwaukee have been trained in CIT — crisis intervention training. And those are the talents and the ideas of how to handle something or somebody that’s in a crisis: how do you talk to them, how do you deal with them, how do you get them into a safe situation or how do you move them on to somewhere where they get the help that they need? And I think that’s always going to be important. I think the police are always going to be involved in that, but the police need to have specialized training for that.

Right now, I’m working with a couple of faculty members on campus, and I think those opportunities would exist in Elon. We’re looking at the intersection of police and dealing with autistic people and students. We’re also taking a look at the intersection of race and autism in creating a situation where a number of officers — I think we have up to four — they’re going to become instructors, along with others, on how to train police on dealing with that. So I think we’re always going to be there. But then there also needs to be the after-action communication ... So if we dealt with somebody that was in crisis — that maybe they had suicidal ideation, but it wasn’t to the point where they had to go to the hospital, they [the student] had a safety plan, the officers work with them, the residence hall staff was aware that the person was okay, there wasn’t an imminent danger — we still share that information, say, with the counseling center … It’s really the specialty of the police to deal with such a crisis intervention, but then sharing it with the appropriate people to also have a follow up, to make sure that the student is taken care of.

What do you think the connection with Elon students looks like in your new position? How do you hope to interact with the student body?

One of the pillars of what I do as a police chief is a real heavy focus on community engagement. And I think there’s a difference between the community engagement and community policing. I think sometimes people meld those together, but they’re really two separate things. The community engagement [is] the police being involved in events and attending events or creating events that we partner with students on. The community policing side, it’s based on those relationships you build: how do you address problems that might occur on a campus where you’re working with those partners and those partnerships that you built up? And those are the two different things. But you can’t do community policing unless you’ve built up partnerships. So the model that I brought with me to UW Oshkosh, and UW Milwaukee and I bring with me to Elon is the motto of building relationships [and] protecting community. And I train my staff to know that you can’t be successful in law enforcement without building relationships.

Sir Robert Peel came out in the beginning and said that the police are the community, the community are the police. It was really that initial idea that you are part of the community, but you can’t police a community without that partnership with them. So, working with the police department on the community engagement side and creating those events. And I think even in my interview, I talked about coffee-with-a-cop type events. And those are really important because it builds those positive connections where we’re not seen because somebody called us and there’s a problem. We’re there because we want to partner, and we usually target different groups and say, ‘Hey, will you partner with us on this event?’ And we target different student groups; we’ve done everything from Asian Student Union, Black Student Union, Student Government, African American Faculty Staff Council, and then we build off of those.

We have those coffee-with-a-cop [events]; it doesn’t mean others can’t attend. But we always have core groups that we work with, and then police officers show up, and you have these unofficial, low stress conversations so people can get to know the police by who they are — their first name. The police get to know them personally. And then you can build partnerships off of that, where if you’re going to do a community policing thing — say there’s a problem where there’s thefts on campus, or harassment, or you have an event or even a speaker coming — you already have these core people that you’re working with, and say, ‘How do we address it? How do we make sure students are safe? How do we work with them to plan the event,’ that type of thing. So I’m really big into that collaboration partnership piece.

And how do you plan on connecting with marginalized communities on campus?

I think it’s important early on, and I know the pandemic will impact this some because you’re just not as free to meet, … but I think what police departments and police chiefs have to do is work on that in the front end. I think what police departments run into sometimes is they manage by crisis. So, something happens on campus, and then you decide that you’re going to go meet with … marginalized groups and things like that on campus. I think it’s important to reach out, have those partnerships and have those positive partnerships, where, if something does happen on campus, they already know that they can reach out to Chief Joe, or to the captain, or an officer — they know them personally, and you reach out. We’re not only there when something is poorly happening or something’s in crisis. We’re there all the time, 12 months a year. But then we’re especially there if something was going on.

When you go to events, you’re not there only for security. Sometimes we go to those events because we’re supporting whatever the event is. I used to get invited and go to lavender graduation for the LGBTQ Resource Center — they had a special lavender graduation — show up and support, congratulate their success, congratulate their graduation. Sometimes you’re there to participate in events, sometimes you’re there to support the event. I think that goes a long way toward letting people know that [we] care as a police department. Sometimes we have to enforce the law, sometimes we have to investigate things that happen, but we’re also here to make sure you’re safe, and you’re successful, and your goal is to graduate and move towards whatever your career might be after college.