Freshman Sakura Kawakami’s first experience in the U.S. was move-in day at Elon University. After settling, she faced culture shock, especially from new student convocation. Kawakami said she was expecting a welcome from the Indigenous tribe whose land the university is located on, but she found that part of the ceremony missing.

“There was none of that during convocation day. There was no acknowledgement of the Indigenous tribes,” Kawakami said. “My father and I — we were shocked.”

Kawakami attended opening school ceremonies like this before, after living around the world throughout her whole life, but she said those ceremonies always included a land acknowledgement. Since joining Elon, she made it her mission to educate others on the issues Indigenous people face like recognizing land.

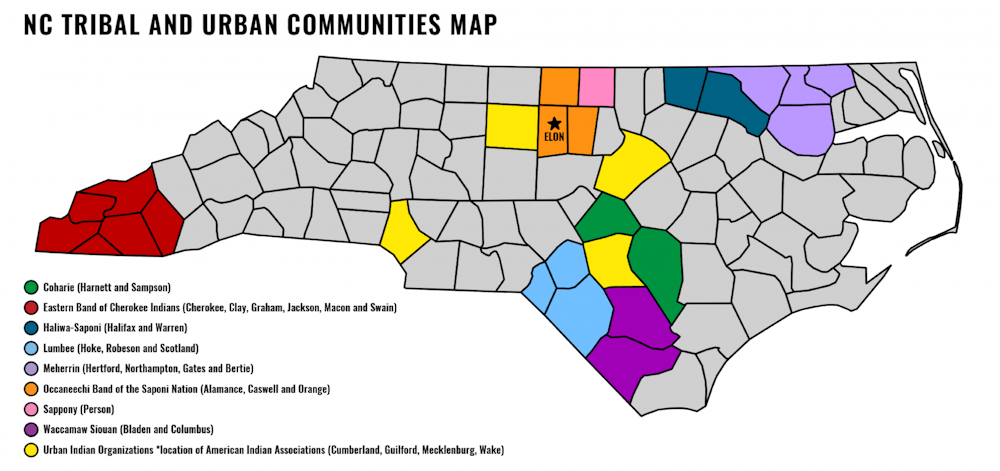

“We are not from here,” Kawakami said. “This is not our land, and we're only visitors to their land, so it's important that we educate ourselves on who the Occaneechi people are, why they're here, how long they've been here, for a little bit about their history, their present, their future.”

Kawakami is a member of the Māori Te Arawa and Ngati Porou iwi, an Indigenous tribe of New Zealand. She currently serves as the president of Elon’s Native American Student Association which is where she plans to bring awareness to a major issue — recognize the Occaneechi tribe and Indigenous community on campus.

According to Paula Patch, NASA’s adviser and professor of English, the organization has about 13 people on its roster, but only four to five members are active. Patch said she feels the organization is an important space to have on campus, even with low attendance.

NASA mainly functions as an internal group to talk about problems people have noticed and then to advocate for the change they want to see. Part of this is to increase land acknowledgements on campus events.

Paula Patch, adviser of Elon's Native American Student Association and professor of English, sits next to reflective art she keeps in her office done by student Anna Derr for a project in Patch's Native American Literature class in Fall 2022.

Patch said Kawakami felt so strongly about her Indigenous heritage that as soon as Kawakami came to campus, her dad reached out to Patch after seeing her role with the organization. It was important for Kawakami to get involved in NASA.

“One of her goals, and she's done this really well, is to find and meet every Native American identified student on this campus,” Patch said.

From the Occaneechi Tribe

Vickie Jeffries, a member of the Occaneechi Tribe and an Alamance County native, serves as the tribal administrator for the Occaneechi Tribe. As the tribal administrator, each day looks different for Jeffries. Some of the work she does for the tribe includes scheduling monthly tribal council meetings, writing grants and planning workshops for the tribe. Jeffries described her role like running a household and keeping everything running smoothly for the tribe.

Jeffries said that Elon students have regularly interacted with her as the tribal administrator, either on campus or on the tribal grounds. Students have done community service at the tribal grounds and Jeffries said she’s been asked multiple times to give a welcome on behalf of the tribe for events at Elon, but not new student convocation.

Jeffries said she’s led classes on basket weaving and beading classes at Elon and hopes in the future for the university to continue to support Indigenous students even more. One thing Jeffries said that she’d like to see in the future is a room in the Moseley Student Center dedicated to Indigenous students, like the Black Community Room, Asian and Pacific Islander Community Room, Gender and LGBTQIA Center and the Center for Race, Ethnicity and Diversity Education all located in upstairs Moseley.

“Elon has been a great supporter of Occaneechi and we’re going to continue that collaboration working with everybody,” Jeffries said. “Hope to continue that relationship on a bigger scale.”

Crystal Cavalier-Keck, an Alamance County native and Indigenous activist, is also part of the Occaneechi Tribe. Since living here, though, she said she’s faced racial discrimination and was recently shocked over a different form of Indigenous hate she witnessed. Cavalier-Keck was outraged by an auction at the Mebane Antique Auction Gallery in March that was selling an Indigenous person’s skull.

“We caused a scene,” Cavalier-Keck said. “You don't buy bones of people or their spiritual items or their regalia because that belonged to the person who had a right that's their spirit.”

Cavalier-Keck gathered a group of other Indigenous activists to protest its sale, where they were able to stop the bidding close to $2,000.

Cavalier-Keck has always been an activist. When she was 16, she sued Alamance-Burlington Board of Education because she wasn’t accepted into the National Junior Honor Society, despite having a high enough GPA. Even when she advocated for her own representation, the media reporting on her lawsuit misreported her race and identified her as Black.

“Most of our community had to hide who they were and so when I sued the school system, it would have been historic if I could have stood proudly and showed my heritage of Native American and African American,” Cavalier-Keck said.

Randy Williams, vice president and associate provost for inclusive excellence, has been working with both the local Indigenous community and Indigenous students on campus. Williams focus is on a large language revitalization project which began in January, when Indigenous author Tommy Orange visited Elon. At this event, Elon invited leaders in the local Indigenous community, including Jeffries, to give a welcome in their native language. Williams said hearing the native language was powerful, because of the history and culture it represents.

“It was really rare for us to hear someone to speak with authority on this particular language,” Williams said. “It’s a rare language and it’s struggling to maintain its circulation in our contemporary society and so to hear our rare language spoken with such authority was a treat for anyone's ears.”

Williams said another part of this project to help make Elon’s campus more welcoming for Indigenous students is to create signage around campus highlighting the Occaneechi language and history. He has also been working on sharing more resources with the Elon community and is working on developing a website that will include land acknowledgement to say and guidelines on the acknowledgement.

“We are stewards of this land,” Williams said. “The whole concept of owners of the land is something that is foreign to the Indigenous community is more of us being good stewards of the land so we share and live in harmony with one another. … It's been really helpful to sort of shift your thinking and expand your thinking about people's lived experiences.”

He said in the future, a room in the CREDE dedicated to Indigenous students is possible, and he is first working on helping grow the Indigenous student population. He is starting this effort by working to make Elon a place more Indigenous students would want to attend. For Williams, the most important aspect of this project is maintaining the relationship with the Indigenous community and taking the time to understand the history and language of the Occaneechi Tribe.

The next steps

Since coming to campus, Kawakami said she has only met four or five Indigenous people, including sophomore Aubee Billie. Billie, a member of the Seminole Tribe in Florida, said part of why she came to Elon was because of the Indigenous communities in the surrounding area, however, she was surprised by the lack of Indigenous and students of color who attended the university.

Billie said while land acknowledgements don’t erase the pain that Indigenous communities have been through, she also feels they are a good place to start. Part of what makes them so important is because the land is significant, particularly to Indigenous communities.

“Land acknowledgements can only do so much,” Billie said. “Having that as a foundation, and understanding that there were people before us on this land, and now a lot of the sacred land is taken away because of colonization.”

Cavalier-Keck said she has been a guest speaker at Elon three times and hopes to share her message with students. She hopes students are aware of the land they reside on and educate themselves beyond a piece of paper of a land acknowledgement.

“What are you actively doing about the land?” Cavalier-Keck said. “Are you going to talk about it? Are you going to help address the issues of invisibility of Native Americans in the U.S.?”

Kawakami is currently working on planning an event to recognize May 5, which is the National Day of Awareness for Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women. NASA will partner with the GLC for this event which will be a stepping stone to more events on campus. Kawakami said she’s optimistic about the work she’s been doing with NASA to help educate the rest of the student body on Indigenous culture.

“It's really important that we establish that organization a little bit more,” Kawakami said. “We're trying to find these long term relationships and what can we do with the tribes so that there's more presence.”