After 33 years working in Hollywood — garnering two Emmys, eight Emmy nominations and 104 credits on IMDb — Dean Jones returned home to Alamance County eight years ago.

Jones considered himself lucky to have the ability to follow his passion in California, but leaving his family was the most difficult decision he ever had to make. He missed a lot back home — including the death of a family member.

“If you grow up here, you leave New York or leave LA to go work at Hollywood, you've left everybody, and you miss a lot of time,” Jones said. “I realized how important family is, but I didn't realize how impactful it was to miss out on their lives until somebody died, and then think of all the stories that you missed out on and could have known about.”

Jones would return to Alamance County every year to produce the Original Hollywood Horror Show — North Carolina’s oldest and largest haunted house. When he would come back home, he remembered just how much he loved North Carolina.

“This is my home. This is where I was inspired. Everything about this state inspired me — the beaches and the mountains, the cities to the country,” Jones said. “My imagination grew here.”

However, Jones said he felt like he had to move to California to continue his career.

“The sad thing about being an artist and living in North Carolina — you have nowhere to make a living,” Jones said.

Because of his hardships moving away to find work, Jones saw the need for a local film school in Alamance County to build the labor force in the state.

North Carolina Film & Television Working Arts School

Jones said he believes that to get into the industry, people don’t necessarily need schooling, so he knows the lessons taught at the school need to be strategic.

“100% of your success in this film business is your work ethic. You don't have to have any skills, any talent. As long as you got the drive and ambition, you'll make it. I've seen that over and over,” Jones said. “If I have a school that's focused and driven on work generating students, we're going to be successful in every way possible.”

Jones’ film school — the North Carolina Film & Television Working Arts School — will start its first semester with five students Jan. 21, 2025. Two classes — Introduction to Screenwriting and Introduction to Film — will be offered on Tuesday and Thursday evenings with a total tuition cost of $1,210. Students can also participate in a work program to pay off tuition after graduation.

Elon University’s cinema and television arts program is the only other option for film studies in Alamance County, allowing for either a Bachelor of Arts or Bachelor of Fine Arts degree.

Jones said the issue with a lot of film programs at universities is that they do not have any contacts for students to get jobs after they graduate. For an industry that works on connections, film students should be working on larger films to carry on a career.

“When you graduate, Hollywood’s not going to hire you because they got their own department. You'd be a background player. You might be a productive assistant. Even the internship program they have, you're somebody's assistant, or you're running coffee or running scripts out,” Jones said. “It's about how, again, having the gumption to stick Hollywood out.”

Jones said a lot of what students learn about production is done on set, not in a classroom, so his lessons will put an emphasis on the history of film, including cinematography, sound and style. There are specific tracks including for those looking to act and write.

Jones is no stranger to teaching. When he moved back to North Carolina, he hosted a scriptwriting workshop. He gave groups four words — marry, Jeffery Dahmer and crayon — and asked them to write a pitch for a movie.

“Wow, I was blown away,” Jones said.

The group continued to meet as a script workshopping group and is currently working on two scripts that will be filmed in Alamance County.

North Carolina’s Film Industry

North Carolina became a notable state in the film industry in the 1980s after hits such as “Dirty Dancing” and “Weekend at Bernie’s,” both filmed in the state. The state has hosted Blockbuster hits like “Iron Man 3” and “The Hunger Games” and more mid-sized productions, such as television series “The Summer I Turned Pretty” and “Outer Banks.”

Starting in the early 2000s, the North Carolina Department of Commerce offered tax incentives to drive the industry, but in 2014, lawmakers changed the law to provide a 25% rebate. The rebate — named the North Carolina Film and Entertainment Grant — awards a total of $31 million per year to each movie and show that meet the minimum spending requirement.

North Carolina has seen large variances in the success of the film industry. After the rebate law went into effect, the industry dipped. Attributed to a post-COVID boost, 2021 saw the highest revenue from the film industry in the state, bringing in $416 million and more than 28,000 jobs. However, that number has declined since.

For 2025, three films and three series were awarded the grant that will bring an estimated $172 million in spending to the state and create 8,500 jobs.

Director of the North Carolina Film Office, Guy Gaster, said the film industry is a great way to immediately grow the economy in the state.

“These types of projects are ones that once they come and they're on the ground, they are infusing large amounts of cash into the local communities,” Gaster said. “They're spending money and they're hiring people and making a positive impact in the community. So that's certainly a unique aspect of this industry that other industries don't have.”

Jones said with the movies he has produced in Alamance County, he has spent $1.4 million that has gone into the local community to restaurants, hotels and other departments.

Gaster said the industry is clearly growing with the additions of major production facilities popping up around the state, including the 40,000 square foot Dark Horse sound stage in Wilmington.

“Not only are we seeing more productions come, but we're starting to see some major investments in our infrastructure, and coupling that with now there's a statewide workforce development program that's being run by the film partnership of North Carolina,” Gaster said. “There definitely is some upward swings to continuing this industry in the state.”

Jones said he enjoys filming in North Carolina because he can go from the 1700s to skyscrapers within 30 minutes of each other.

“We got little pockets that represent different time periods and different eras in terms of architecture,” Jones said. “I can go from the 1700s to present day, with any time period based on the locations we have locally.”

The North Carolina Film Office has over 5,000 filming locations listed on their website, including 50 locations in Alamance County.

Jones said the North Carolina film industry is a much better environment to work in because it lacks the pressures of Los Angeles, where he would constantly be competing with his peers.

“They’re all trying to drag you down. If you climb up the ladder, somebody's behind you, pulling your leg right back down. You're getting pulled down towards your arm, and you get beat down all the time by your own peers,” Jones said, “Here it's more comfortable laid back. It's my home state.”

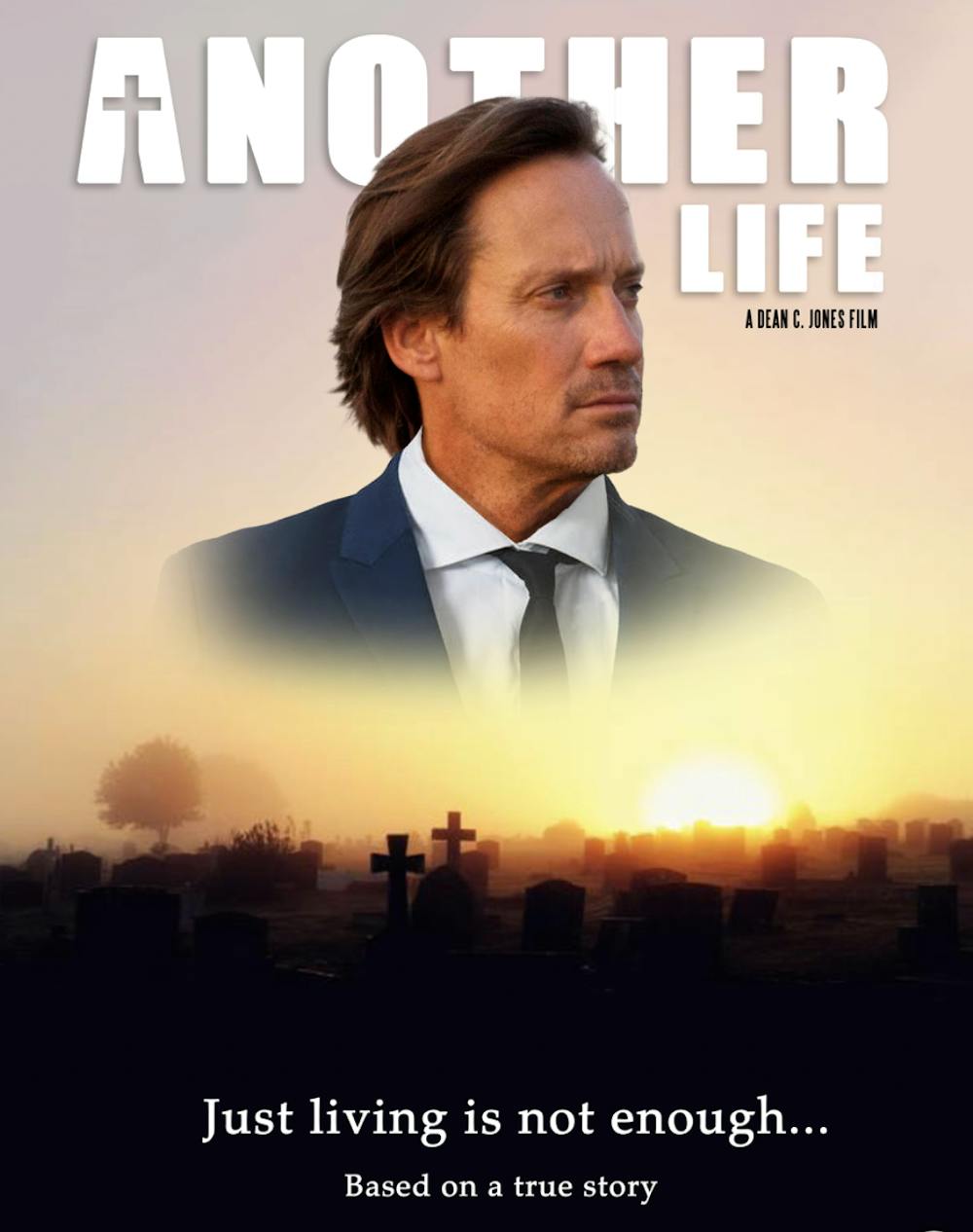

Currently, Jones is finishing up “Another Life” — a story about a funeral director turned stand-up comedian — which he wrote, produced and directed. Filming wrapped in November, and the movie will be having a theatrical premiere in select cities around the world in the near future.

Jones is already looking to his next projects with the help of his writing workshop, which will be shot with the help of the upcoming class in the spring.

While Jones is working on building his legacy, he is working to make his dad proud.

“He was always nudging me toward film, and I got where he wanted to be sat. He watched me, and he lived vicariously,” Jones said. “He saw his son get to the Emmys eight times.”